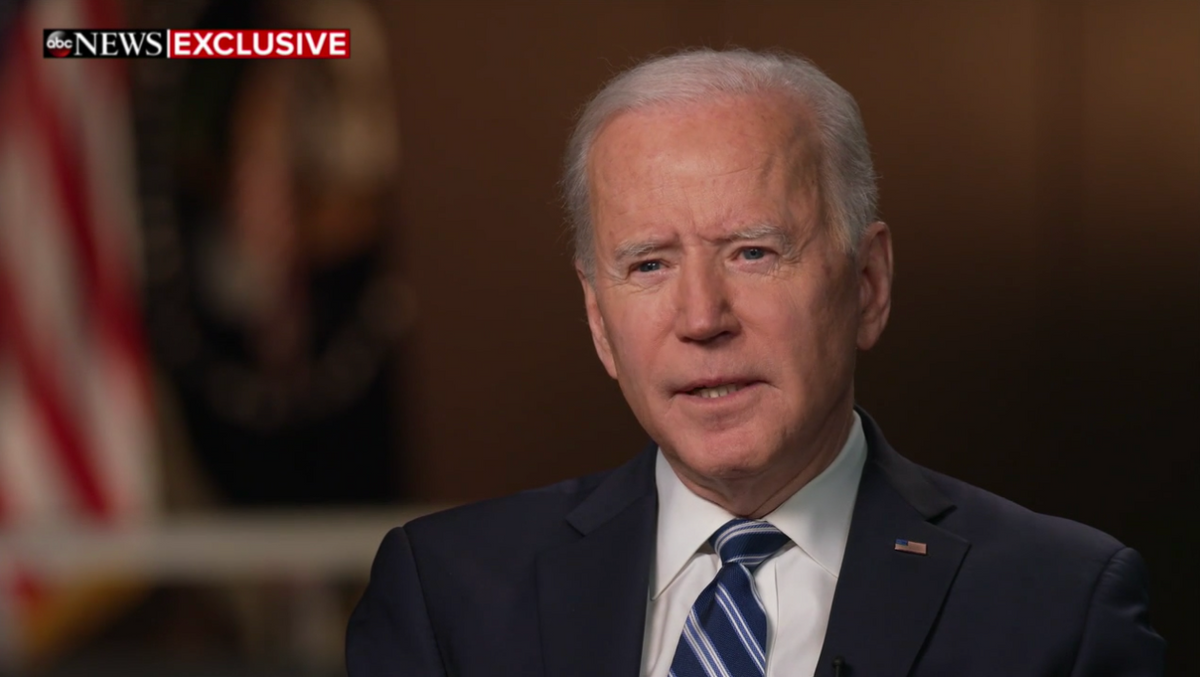

"I don't think that you have to eliminate the filibuster," President Joe Biden said in an interview with ABC's George Stephanopoulos. "You have to do it what it used to be when I first got to the Senate back in the old days….You had to stand up and command the floor, you had to keep talking."

"You've got to work for the filibuster," he added.

His remarks are now the talk of Capitol Hill. These words may wind up being some of the most consequential of the Biden presidency—but it depends on what he actually means.

Biden has raised the possibility of returning to what's commonly known as the "talking filibuster," popularized and somewhat misrepresented by Jimmy Stewart in Mr. Smith Goes To Washington, and still not very well understood by most Americans. But there are two types of talking filibusters, only one of which might actually force the GOP to back down from stopping legislation.

A bit of where we are now, and then a bit of where we were, might help explain.

Where we are is in a state of gridlock, where a simple raise of hands from at least 41 senators who will vote against a motion to end debate—what's known as "cloture"—effectively means that a bill dies on the vine. They don't have to talk. Indeed, they don't have to do anything at all except indicate their lack of support. Thus a minority of 41 can hold hostage all Senate legislation (except for those related narrowly to the budget under special rules developed just for revenue raising and spending).

The anti-majoritarian filibuster rule came into full fruition because, back in 1970 and just a few years before Biden became a Senator, the body grew tired of having business held up by talking filibusters. The rule change provided for a two-track system in which the Senate's business could continue, by unanimous consent or consent of the minority leader, even while "debate" on another matter was held open by at least 41 senators.

This effectively meant that the Senate could carry on business per usual, and no one even would have to physically be present to keep debate open or vote for cloture during a pause. No one expected that the two-track system would open the door to widespread abuse of the filibuster.

Before the two-track system was put in place, filibustering senators literally would have to "hold the floor." That is to say, they would have to keep talking without interruption in order for debate to stay open. A group of Southern senators opposed to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 actually filibustered for a record 60 days before a cloture motion finally prevailed. This ugly display reinforced the belief, common still today, that the filibuster mostly has been used throughout history by racist senators to stop civil rights protections for minorities.

The two-track system put in place in 1970 destroyed the whole purpose of the filibuster, which was originally intended to draw attention to an objection and then inconvenience the body so greatly as to force compromise. After 1970, with neither attention drawn nor inconvenience imposed, the filibuster morphed into a way for the minority to hold up legislation with a simple raise of hands. In the 52 years before the two-track system was adopted, from the first modern filibuster in 1917 until 1969, only 58 cloture motions were filed. In the 51 years since 1970, there have been more than 2,200.

With both President Biden and Senator Joe Manchin recently indicating they would be open to reforming the filibuster back to how it was, this could mean elimination or at least reform of the two-track system. For example, a bill might be "two-tracked" only by a majority vote of at least 51 senators, and not by consent of the minority leader. That would mean the Dems could force the GOP to actually take up Senate time with any filibuster. Further, filibusters could require the GOP to talk continuously in order to keep debate open. Most of the American public believes this should be the rule, and many mistakenly believe it still is. Under the old rules, however, the senators could conduct their filibuster in shifts, as they did in 1964. Some within the GOP perversely might really like this, as it would create an opportunity for political spectacle for their supporters and allow for excessive political grandstanding.

But in theory, should the Dems want to truly be in the business of actually reforming the filibuster, Joe & Joe could go one step further. Under a proposal being floated from Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR), an entire group of 41 senators would have to hold the floor together and keep talking continuously. Eventually, Merkley explained, one of two things will happen: The majority party will lose its nerve and pull the bill, or the number of senators present will fall under 41 and enable the majority to advance the bill with a three-fifths majority. That would up the stakes incredibly. The test would thus become whether the Dems want the legislation passed more than the GOP wants to block it.

Senators may not be too keen to exert themselves in favor of an obstructionist cause. Senator Ron Johnson recently required the entire pandemic relief bill be read into the record, with only a skeletal crew of GOP senators there to keep the delay going. This allowed one intrepid Democratic senator, Chris Van Hollen (D-MD), to move in the dead of night, once the reading was done and the GOP senators had all left, to shorten debate from twenty hours down to three, wholly undoing Johnson's delaying tactic. This is a perhaps a preview of how the old filibuster rule might play out if reinstated.

The upshot of Merkley's proposal, if put forth by senate leadership, is that the filibuster would be used far less frequently. The nightmare of a long, protracted battle with a number of elderly senators unable to leave the chamber for weeks at a time seems too much for either side to stomach. It would actually force both sides to pick their battles carefully and compromise far more—precisely what Senator Joe Manchin says he wants to see.

Whether Senate holdouts Manchin and Sinema actually are willing to go down this path remains unclear. Manchin recently reiterated his general support for the filibuster and his opposition to axing the 60-vote requirement. But with both sides rattling sabers, some kind of compromise is more likely now than before.

For example, Majority Leader Schumer could merely threaten to bring back the talking filibuster unless McConnell agrees today that legislation relating to civil rights, or specifically to elections and voting, be exempted from the filibuster rule. Now that the idea of the talking filibuster is very nearly on the table, it opens the door for leverage that the Dems simply did not have before.

Let's hope they understand this and use it well.

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads