fungus

Top stories

This Soil Fungus That Eats Plastic Could Change How We Dispose Of Waste

A research team took samples of waste from a Pakistani landfill site and found that a type of fungus can break down a common plastic polymer.

While extracting samples from a Pakistani landfill site outside of Islamabad, researchers discovered a soil fungus that feeds on plastic.

It is no surprise that landfills around the world contain tons upon tons of plastic. When combined with the oceans’ contents, the number reaches into the billions of tons — and humans continue to produce plastic in factories daily, despite efforts at recycling and creating reusable substances.

For this reason, the human race has introduced what is called the Anthropocene, a new geological epoch caused by ample changes to the planet, warranting the classification from the former Holocene. The sheer number of plastics produced, as well as the abundance of concrete structures around the world, carbon pumped into the atmosphere with regularity and phosphorous and nitrogen permeating the Earth’s soil represent this new change — though they are also a large part of its cause, as scientists believe.

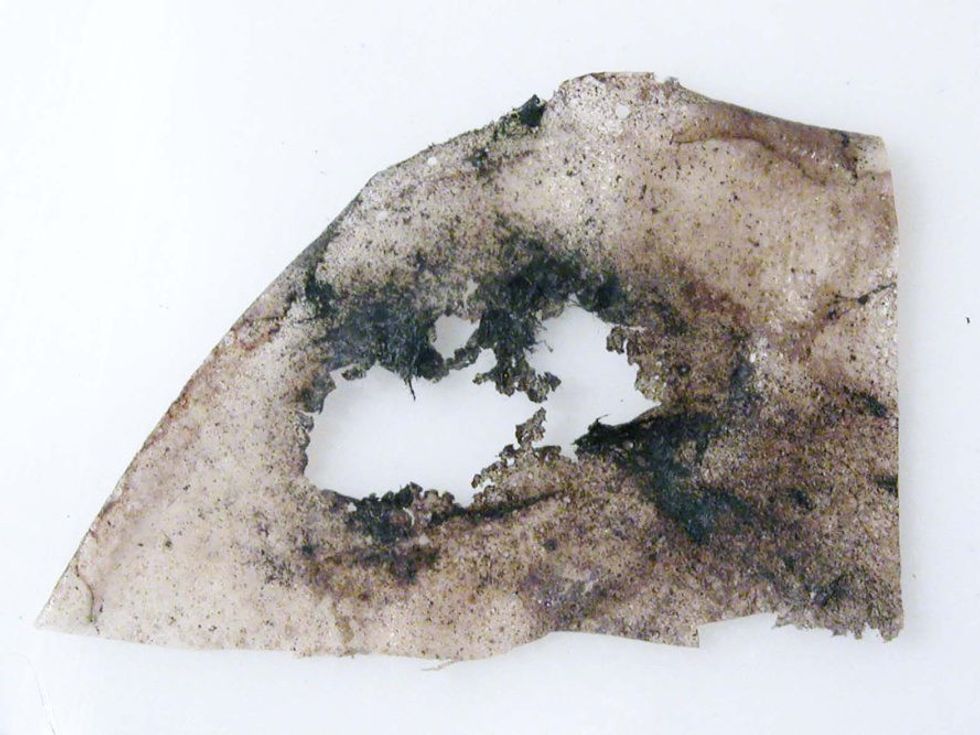

But back to landfills: one remarkable, but not wholly unexpected, effect of the Anthropocene is a species of fungus called Aspergillus tubingensis, which degrades plastic by feeding on it. In lab experiments, Aspergillus tubingensis mycelia, or the branched, tubular filaments of the fungus, seize the polyester polyurethane plastic, engendering a breakdown and scarring of the plastic’s surface. These results were published in Environmental Pollution, volume 225 in June 2017.

Organisms have fed on plastic waste in prior instances, so this particular finding in the Pakistani landfill site is not the first.

Plastic-degrading bacteria uncovered both most recently and in the past accompany another, larger discovery from earlier this year: the wax worm, which can naturally deteriorate plastic because of its similarity to beeswax, the worm’s typical and natural food source.

These findings, and the increased speed with which they are happening raise an unusual question: how can we potentially harness these organisms and this worm to combat the massive and regular plastic waste creation? As humanity has never experienced such an opportunity regarding plastic degradation, environmental and biology researchers do not currently have answers.

Dr. Sehroon Khan, of the World Agroforestry Centre and Kunming Institute of Biology, who led the Environmental Pollution study, explains, “Our team’s next goal is to determine the ideal conditions for fungal growth and plastic degradation, looking at factors such as pH levels, temperature and culture mediums.”

The team found that — though this testing is still in early stages — following two months in a liquid medium, Aspergillus tubingensis had degraded a sheet of polyester polyurethane to the point of near-dissipation. It degenerated the polyurethane better under these conditions than on an agar plate and when buried in soil.

According to the study abstract, “Notably, after two months in liquid medium, the PU film was totally degraded into smaller pieces.”

There is a downside: plastic generally remains on the planet as long as it does due to its inert state. Because it is so often chemically inert, it is also usually sterile. Humans use plastic to package food, build airplane and car parts and even as a component in pacemakers and the primary component in condoms. This means these new microorganisms and organisms with these new abilities are evolving in a way that could eventually threaten the integrity of plastics humans need and regularly use.

The Aspergillus tubingensis fungus was also spotted in the airways of patients with lung disease, which could have dangerous implications on human health if administered irresponsibly.

Despite health concerns and worries for the future of plastic degradation, these findings reveal creation of environments never before seen on Earth, and once again, the planet’s resilience.

“This could pave the way for using the fungus in waste treatment plants, or even in soils which are already contaminated by plastic waste,” says Dr. Khan.

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads