background checks

Top stories

For most of our country’s history, the regulation of firearms was not a contentious or even controversial issue. Before the 21st century, both federal and state laws regularly limited the possession and use of guns through regulations, licenses and restrictions on who could possess them.

Because of the plain text of the Second Amendment, which begins with the phrase, “A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State,” for some 200 years of our nation’s history, judges normally interpreted it to protect only those arms and activities having some connection to an organized “militia.”

Indeed, the Supreme Court directly addressed the language of the Second Amendment only once before this century. In a decision involving the prosecution of a gangster accused of transporting a short-barreled shotgun in violation of the National Firearms Act of 1934, the Court had no issue holding in United States v. Miller that because a short-barreled shotgun was not suitable for use in a militia, its possession was not protected by the Second Amendment, and Miller’s indictment was therefore lawful.

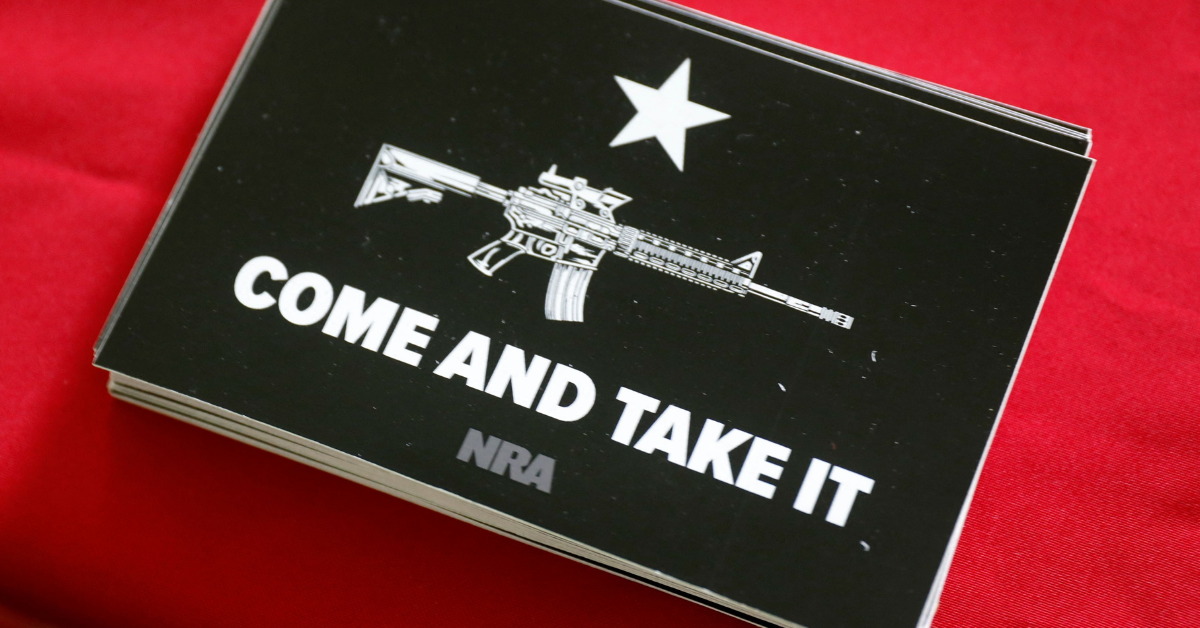

But as the political power of the National Rifle Association grew over the past decades, and its mission went primarily from gun safety and responsible gun ownership to unfettered access to all manner of weapons, Republican politicians who received massive campaign contributions and their appointed conservative jurists began to do the bidding of the gun sales lobbyists.

This resulted in a long campaign to transform the Second Amendment into something that many say was never intended: an unrestricted right for private individuals to purchase, carry and use even the most dangerous kinds of guns.

While it seems common to assume that the Second Amendment gives citizens the right to buy and keep guns, that is a relatively new development. The key case was decided only as recently as 2008.

District of Columbia v. Heller was a 5-4 opinion by the late Justice Antonin Scalia that threw out the prior nexus between gun regulation and “militias” and found, for the first time, that a D.C. law that restricted unlicensed, functional handguns within private homes violated the Second Amendment’s right to keep and bear arms.

Scalia wrote:

“The Second Amendment protects an individual right to possess a firearm unconnected with service in a militia, and to use that arm for traditionally lawful purposes, such as self-defense within the home."

Many historians point out that this was quite the heavy lift, as the text of the Amendment and the historical record suggest. The primary purpose of the amendment, they note, was to prevent the need for the U.S. to have a professional standing army, and that it was never about the right of private individuals to keep weapons.

But the Heller case nevertheless found that the Amendment created a personal right to bear arms in self-defense, enshrining that as an enumerated constitutional right and thereby making it much harder for the federal government to restrict it. Because the D.C. law at issue was under federal jurisdiction, the Court found the law as written violated the Second Amendment.

Scalia acknowledged, then waved away, concerns that lawmakers and law enforcement had with respect to a possible rise in gun violence.

He wrote:

“We are aware of the problem of handgun violence in this country, and we take seriously the concerns raised by the many amici who believe that prohibition of handgun ownership is a solution."

“The Constitution leaves the District of Columbia a variety of tools for combating that problem, including some measures regulating handguns."

"But the enshrinement of constitutional rights necessarily takes certain policy choices off the table.”

Scalia did not mention it was his decision that did the enshrining.

Legal observers and experts have blasted the decision. Sparing few words, former Chief Justice Warren Burger criticized the very idea the Constitution grants an individual right to bear arms.

Burger declared:

"[The Second Amendment] has been the subject of one of the greatest pieces of fraud, I repeat the word fraud, on the American public by special interest groups that I have ever seen in my lifetime.”

And Justice John Paul Stevens, who wrote one of the dissents in Heller, called it:

“unquestionably the most clearly incorrect decision . . . announced during my tenure on the bench.”

It took the new conservative majority on the Court only two years to extend Heller’s reasoning over federal gun regulation to the individual states. In McDonald v. Chicago, the Court found that the Second Amendment also protects against state infringement of the newly minted, constitutionally protected right to possess handguns for self-defense.

That meant the states, and not just the federal government, would now have to prove that their gun regulation laws did not run afoul of that right, putting at risk many long-standing gun regulation laws.

The Court achieved this ruling by way of something called “incorporation.” This is a complex legal concept, but essentially it is a way of applying federal restrictions that exist in the Constitution to the several states by leveraging the “Due Process” language of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The question the Court usually asks is whether the right at issue is one of the “fundamental rights necessary to our system of ordered liberty”—which the conservatives claimed now included the right of citizens to keep and bear arms for their personal defense. If it is, then that right is protected against infringement by either the federal government or the states.

(Justice Alito appears to cherry-pick his “fundamental” rights, however, having recently written the draft majority opinion in Dobbs overruling Roe v. Wade by finding the right to abortion is not a “fundamental” one that existed at the time of the Constitution’s drafting—and therefore it can be banned by the states without a violation of Due Process.)

The Court today is on the cusp of yet another potentially sweeping decision on gun regulation. This judicial session, it heard arguments in New York State Rifle and Pistol Assoc. v. Bruen, which is challenging a 108-year old handgun licensing law out of New York.

The law requires anyone who wants to obtain a license to carry a concealed handgun to show “proper cause” for the license to issue. New York courts have said that means applicants must show a special need to defend themselves, rather than simply wanting to protect themselves or their property generally.

The lawyer for the gun association argued the point of a constitutional right is you don’t have to satisfy a government official that you have a good reason to exercise it.

But this isn’t always true. For example, if you wish to exercise your freedom of speech in a public space, you still need to first obtain a permit to gather.

Many states, including Texas, have relaxed their gun laws and now allow teenagers as young as 18 to purchase handguns and assault weapons and its citizens to openly and permitlessly carry weapons.

While there are probably some justices who would like to eliminate the power of the states to place any restrictions on possessing and using a handgun, some of the conservative justices appeared in oral argument to get tripped up over whether the state could regulate the bringing of concealed guns into public spaces, such as subways and Times Square.

While it isn’t clear how far the solid conservative majority will now go to strike down long-standing gun regulations by extending Heller and McDonald, it is abundantly clear that such laws are now on the defensive.

Gun advocates are pressing their advantage accordingly in the courts and in state legislatures, even as the number of mass shootings and deaths rise precipitously.

Meanwhile, the NRA’s lock on the Republican party continues; in the Senate there are not even 10 GOP votes out of 50—providing the 60 needed—to advance popular legislation such as basic background checks favored by some 90 percent of Americans.

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads