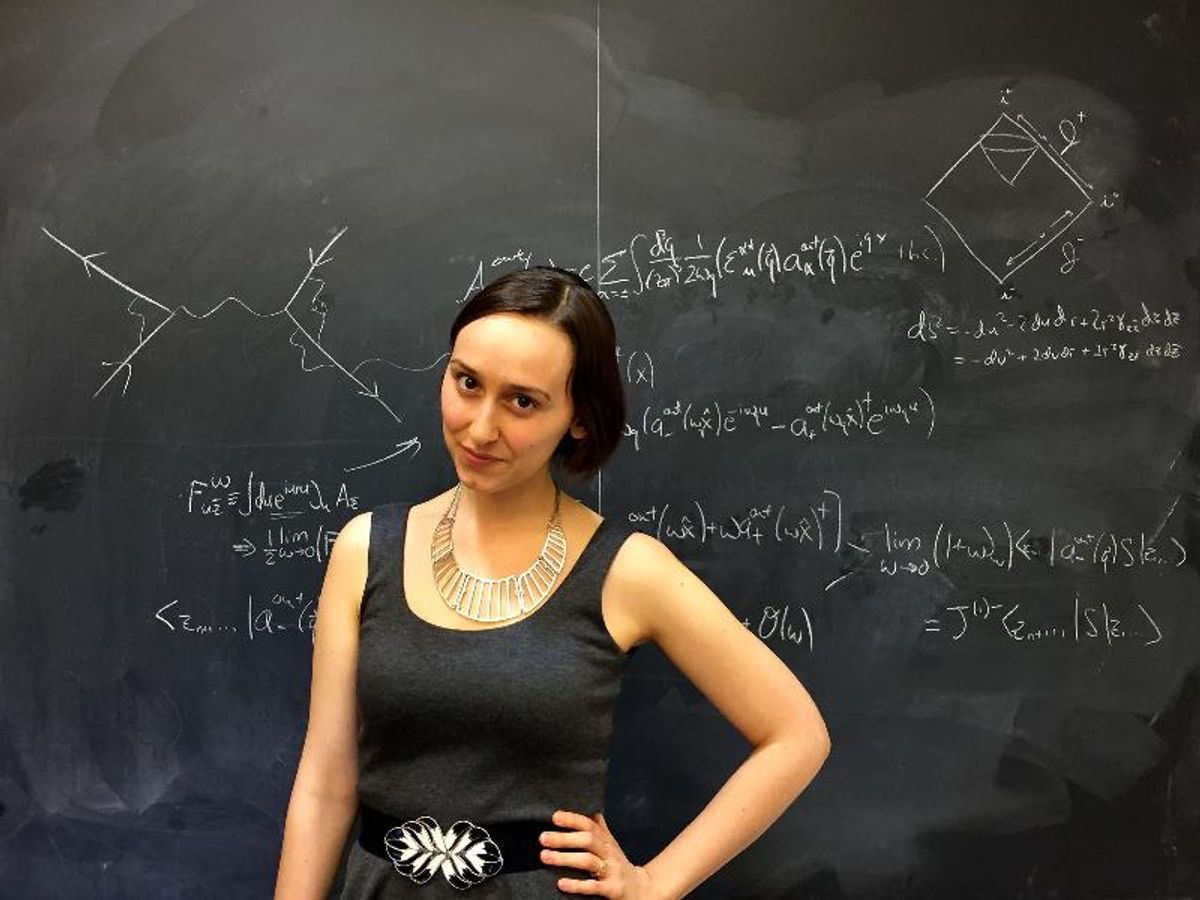

“For me, there are only two kinds of women: goddesses and doormats,” said the 61-year-old Pablo Picasso to his 21-year-old mistress in 1943. Despite the age difference, Françoise Gilot, a talented artist in her own right, went on to become the mother of two of Picasso’s three illegitimate children and spent ten years with the difficult genius.

Picasso had numerous lovers, wives and mistresses throughout his long career. Each new love inspired him, and art historians have determined direct correlations between the start of new love affairs and a change in the artist’s style. A new exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Picasso Sculpture, gives viewers the opportunity to witness how love galvanized his three-dimensional portraits of women and how these muses catapulted his artwork in continuously new directions.

The Fac(e)ts of Life

Picasso had many affairs, but only a handful of women assume a position of importance in his sculptural oeuvre. The first is Fernande Olivier, Picasso’s first long-term lover and the only one who knew him before fame and fortune struck. The pair met in 1904 and fell in love after smoking opium together. Each was 23 and it was the last time Picasso fell in love with someone his own age.

After leaving an abusive husband, Olivier moved to Paris where she became a popular model for several artists, including Picasso. She moved in with him a year later, after which he insisted she only model for him. The collaboration resulted in over 60 portraits during their eight-year relationship, including Head of a Woman (1909), which resides in the show’s first gallery (titled “Early Works and the First Cubist Sculptures”). Created after a vacation in the mountains where Picasso had painted Olivier many times in his brand new Cubist style, many consider the sculpture a seminal work.

Cubism, which was created by Picasso and his friend Georges Braque, dissects an object into small planes, like the facets of a gemstone, and then re-assembles the facets so that it appears as if you’re looking at the object from multiple viewpoints at the same time. Head of a Woman was the first time Picasso realized he could translate Cubism into three dimensions.

Once Picasso began achieving recognition, his interest in Olivier waned. In 1911, he began an affair with a 26-year-old, and the following year Olivier too had an affair. Citing Olivier’s affair as his reason for breaking off their relationship, Picasso left Olivier with no means of

support since they had never married (in fact, Olivier had never divorced her husband) and therefore with no rights to any of his property or money.

It’s All About Sex

Picasso began a series of affairs, twice falling desperately in love and proposing marriage to no avail. Then, in 1917, as he designed the sets for a ballet presented by his friend Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes, Picasso met Olga Khokhlova, a tempestuous ballerina with the company. Picasso courted her feverishly but Olga refused to sleep with him. Diaghilev told Picasso that no self-respecting Russian woman would have sex with a man without the assurance of marriage and so the desperate Picasso proposed. They wed the following year and Olga bore the first of Picasso’s children, Paulo.

As with most of Picasso’s relationships, storms ensued as the socially ambitious (and extremely jealous) Olga tried to tame his free spirit and rein in his capacious appetite. Picasso never divorced Olga although he contemplated it, until he learned that French law would give her half of his estate, including his brushes, sketchbooks and completed works. Despite painting her often, there are no images of Olga in the MOMA show but her replacement appears multiple times.

That replacement, Marie-Thérèse Walter, was the mother of the first of Picasso’s illegitimate children (the artist had four children with three women, only one of whom was his wife). The story goes that Picasso and Marie-Thérèse met outside of the Galeries Lafayette department store in Paris. With his marriage shredding, he was walking the streets of Paris in search of sex (Picasso had a history of visiting brothels). She was 17 and he was 46.

“You have an interesting face,” he told her. “I am Picasso. You and I are going to do great things together.” His name meant nothing to her but she liked his tie and his seductive nature. A week later, she was his mistress.

During the early years of their relationship, Picasso kept her in a flat across the street from his wife. In 1930, Picasso purchased the Château de Boisgeloup, near Gisors, about 45 miles northwest of Paris where Marie-Therese would spend weekdays and then be banished to a

local inn when Olga visited with their son Paulo on weekends. He installed a sculpture studio in the stables and produced more sculptures than in any other period of his life. Many are metaphors for the sexual union between the artist and his model, Marie-Thérèse.

Marie-Therese inspired Metamorphosis II (1928) in the third gallery (titled “The Monument to Apollinaire”) and numerous of the sensual busts in the fourth gallery (titled “The Boisgeloup Sculpture”) including Bust of a Woman (1931) and Head of a Woman (1932). Her freshness and youth inspired him and the voluptuous forms echo her curvy body with its apple cheeks, bulbous nose and ample hips.

Of course, as usual with Picasso, his roving eye soon led him to another woman, Dora Maar, which made Marie-Therese (like Olga before her) violently jealous. Once, the two women met accidentally in the studio where Picasso was painting his monumental masterpiece Guernica. They demanded Picasso choose between them. Instead, he told them to fight it out and so the women wrestled on the studio floor.

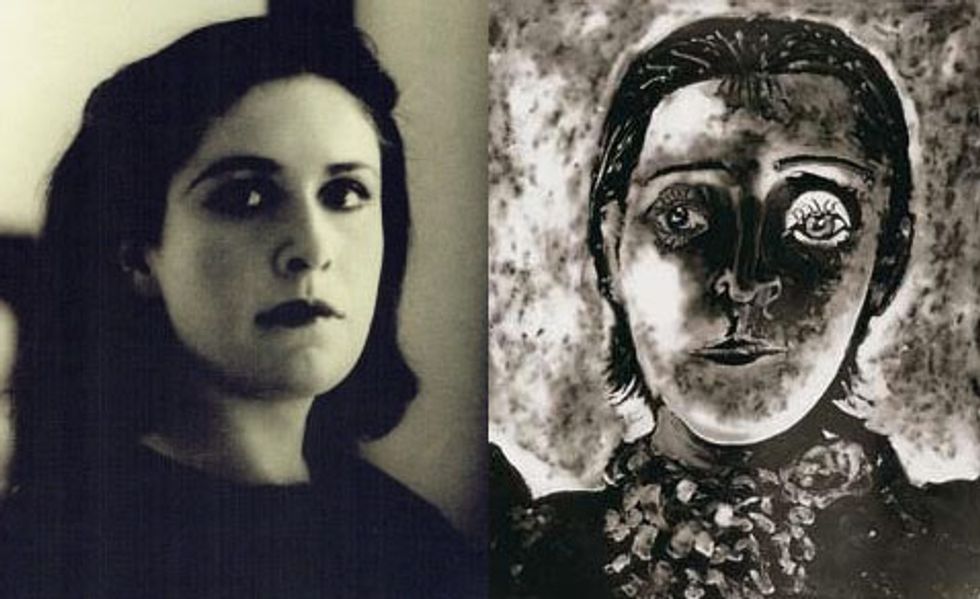

The Crying Woman

Maar herself can be seen in the sixth gallery (titled “The War Years”) in Woman in a Long Dress (1943) in which the shape of the face, high cheekbones and pursed lips are similar to photographs of her.

In the sculpture, there’s sadness in her face and a sense of worry that’s reminiscent of Picasso’s paintings of weeping women from a few years earlier. As the artist said of Maar:

“Dora, for me, was always a weeping woman… And it’s important, because women are suffering machines.”

Born Henriette Theodora Marković, Maar studied art in Paris at the Académie Julian, which was the only school in Paris where women artists could receive the same training that men received at the École des Beaux-Arts. At 29, she met the 55-year-old Picasso while taking set photographs during the filming of director Jean Renoir’s Le Crime de Monsieur Lange.

Picasso didn’t recall the meeting, insisting they met at the Café Les Deux Magots, where he was drinking with one of the founders of Surrealism, poet Paul Éluard. Dora stretched her hand onto the table and began rapidly jabbing a sharp knife between each of her fingers in a way that entranced Picasso. Maar cut herself and Picasso kept the bloodstained glove she wore as a memento of the meeting.

After nine years, their relationship too began to deteriorate, and Picasso took yet another mistress, the aforementioned Françoise Gilot. After the split, Dora left photography behind and devoted herself to painting. She also took up Roman Catholicism explaining, “After Picasso, God.”

In later years, Dora died poor and alone, as did several of Picasso’s women. By then, she had sold most of the works he had given her, their value increased by her ownership. “On the walls of a gallery,” she said, “they are worth only half a million. On the walls of Picasso’s mistress, they are worth a premium; the premium of history.”

One Man’s Trash is Another Man’s Treasure

Françoise Gilot appears in the exhibition in Pregnant Woman (1950) and Woman with a Baby Carriage (1950-54). The former, a plaster statue in the seventh gallery (titled “Vallauris Ceramics and Assemblages 1945-53”), shows a nude woman with large breasts and a distended belly. A large clay pot embedded in the plaster forms her abdomen and two smaller pots form her breasts. Gilot said Picasso made Pregnant Woman as “a form of wish fulfillment” because, after giving birth to two illegitimate children, she refused to have a third.

Woman with a Baby Carriage (in the eighth Gallery, “Vallauris Ceramics and Assemblages 1952-1958”) was started the year after the birth of Gilot’s second child with Picasso, Paloma Picasso. Paloma, named for the dove of peace, has been designing jewelry for Tiffany & Co. since 1980.

The bronze sculpture, like many of the others in this room, is cast from an assemblage of different pieces of metal, such as bits from a baby carriage, cake pans and a stove plate. Picasso found these discarded materials in scrap heaps and rubbish dumps. They represent his bid to make his art accessible to everyone. In her memoir, Gilot acknowledges that the timing of the sculpture coincides with Paloma's birth, but adds that as she walked with Picasso from their home to his studio, she would push a baby carriage so that he could toss in scraps he found along the way.

Another assemblage in the same room suggests Paloma as a Little Girl Jumping Rope (1950-54). Here Picasso used an array of scavenged materials, including a wicker basket for the torso, an oval chocolate box for the face, two clumsy shoes (both for the same foot) and strips of corrugated paper for the hair. With these found objects, he almost accomplishes the impossible by creating a sculpture that appears to defy gravity and almost doesn’t touch the ground.

Putting the Pedal to the Metal

In 1953, Gilot grew tired of Picasso’s unfaithfulness and left him. In the last gallery (titled “Sheet Metal Sculptures”) sits Picasso’s tribute to his next young muse. She was neither wife nor mistress; but not for Picasso’s lack of trying. Picasso first noticed Lydia Sylvette David (she was called Sylvette, as is the sculpture) in the town of Vallauris on the Cote d’Azur where he had a studio. A few weeks later, he presented her with a drawing he had done of her from memory. He embraced her saying, “I want to paint you, paint Sylvette.”

Over three months, he did just that, creating more than forty drawings, paintings and sculpture of the teenager. The works range in style from naturalistic to Cubist. Critics dubbed this Picasso’s “Ponytail Period.” (Sylvette’s high ponytail was the inspiration for the style Brigitte Bardot adopted after spotting Sylvette walking in Cannes.) Unlike the other women in his life, Sylvette never slept with the 72-year-old Picasso—in fact, at 19 years old, she was too timid even to pose nude.

The 24-inch high sheet metal sculpture of Sylvette displayed was the first of Picasso’s folded metal sculptures. Here Picasso once again explored the properties of materials, experimenting and testing to see what he could achieve with sheet metal. He paints it and cut it out in places, emphasizing multiple perspectives simultaneously (much like with his Cubist sculptures) but with completely original results.

Fourteen years after its creation, Sylvette (1954) was enlarged by Norwegian sculptor Carl Nesjär to 36-feet tall and placed on a plaza within the NYU college campus in Manhattan where it resides today. Picasso’s grandson Olivier Widmaier Picasso says that Sylvette also inspired the abstract sculpture that sits in Daley Plaza in the middle of Chicago. Sylvette began painting her own works at the age of 45 and today displays work under her married name Lydia Corbett.

Picasso’s relationship with Sylvette lasted only a few months (perhaps because she wouldn’t sleep with him), and he soon took up with a sales assistant in a pottery gallery. Jacqueline Roque was Picasso’s final and longest-lasting relationship. She was 26; he was 73. The aging Lothario romanced her by drawing a dove in chalk on the wall of her house and by bringing her a single rose every day.

After six months, she relented and remained his lover, muse and loyal assistant until his death twenty years later. She also became his wife (after Olga died in 1955) and Picasso created over 400 paintings and sculptures inspired by her, including Woman with Child (1961), which also rests in the final gallery and includes Roque’s daughter Catherine (being held aloft) from her first marriage. Because Picasso’s other children lived with their mothers, Catherine lived with Picasso longer than any of his biological children.

As the exhibition shows, Picasso’s work evolved constantly over his illustrious career. In the 140 works on display at MOMA, one sees how the great artist repeatedly used each new muse to refresh and reinvigorate his practice. Callous, passionate and self-involved, Picasso had hundreds of affairs. But one thing remains clear: his women inspired him to ever-higher levels of greatness.

“Picasso Sculpture” runs at the Museum of Modern Art through February 7, 2016.

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads