The discovery of artifacts that bear Islamic imagery is raising questions in the archaeological world. Findings in ancient gravesites have raised the question: Did Vikings who raided Muslim communities bring home a new religion, or are modern archeologists seeing interfaith connections as a way to counteract white supremacy?

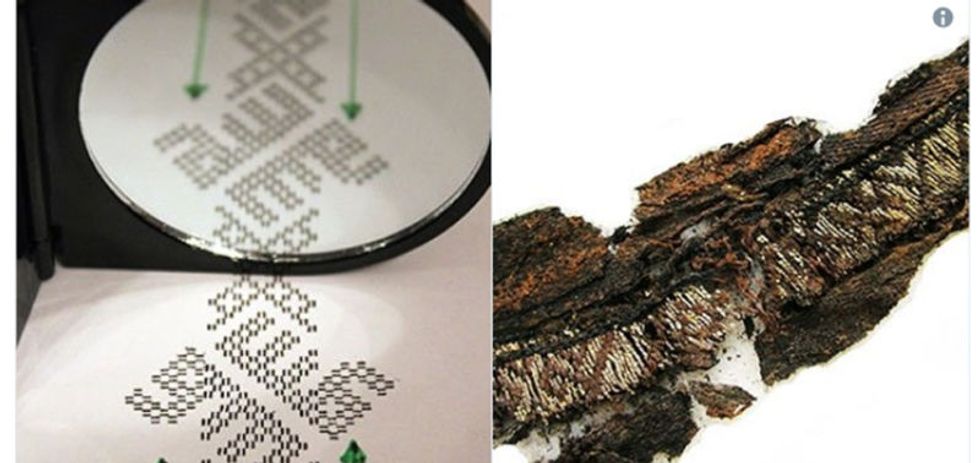

Researchers at Uppsala, Sweden’s oldest university, claim to have found Islamic symbols woven into clothing artifacts found at 9th century Viking burial sites in Birka and Gamla Uppsala in Sweden. An ornate pattern woven into bands of silk on a buried outfit bears a resemblance to the geometric Kufic text spelling out the words “Allah.” Textile archaeology researcher Annika Larsson said at first she could not make sense of the symbols, but then, “I remembered where I had seen similar designs: in Spain, on Moorish textiles.”

The Muslim words for God, Allah and Ali, appear to be woven both forwards and backwards in the decorative woven fabric. Larsson said that Viking burial clothes were selected from the finest and most important items available, rather than everyday fashions, just as modern era people are typically buried in formal clothes. “Presumably, Viking age burial customs were influenced by Islam and the idea of an eternal life in paradise after death.”

The Vikings had extensive contact with the Muslim world, as they traveled widely on their raids and expeditions. Other graves and caches of Viking treasure have yielded over 100,000 Islamic silver coins known as dirhams, jewelry bearing Islamic symbols, and bodies bearing DNA from Persia, suggesting intermarriage and immigration (voluntary or otherwise). In 2015, a Viking woman’s glass ring was discovered bearing the inscription “for Allah” or “to Allah.” Religious objects have been found in Viking graves that represent seven languages and three belief systems, Christianity, Islam, and the worship of Thor, a key figure in Norse mythology.

However, other researchers are unconvinced that these artifacts are meaningful. "The use of Ali does suggest a Shia connection," says Amir De Martino, programme leader of Islamic studies at the Islamic College in London. "But without the phrase 'waly Allah' accompanying the name - meaning 'friend of Allah' - this would not be from mainstream Shia culture and might just have been copied wrongly from something that was," adds De Martino, who is also the chief editor of Islam Today, a British Shia magazine.

The debate has become more heated due to modern political divisions. The white supremacist movement has adopted symbols from the Viking tradition, revering a faux-medieval culture as an example of perfect white purity. The white supremacists who marched in Charlottesville carried equipment bearing Viking imagery. (One popular white supremacist symbol, the Black Eagle of the Holy Roman Germanic Empire, is strongly associated with its patron saint, Saint Maurice, who was actually black.)

This appropriation raises the ire of Viking scholars and historical reenactment enthusiasts, who point out that the Vikings traveled widely and intermarried with people from various races, bringing home people, ideas and imagery from around the world.

"Viking enthusiasts get mistaken for racists and Nazis all the time, and we're very uncomfortable with that. White nationalists don't get to reinvent what Viking culture is," said Solvej von Malmborg, a member of a group called Vikingar Mot Rasism (VMR, or Vikings Against Racism). Larpers, or enthusiasts of Live Action Role Play (LARP), as well as practitioners of Viking martial arts, folk groups, and historians have been dismayed by adoption of medievalism and Vikings cosplay by white supremacists.

“The view that white supremacists have of the Middle Ages is monocultural, mono-racial, and mono-religious; that simply doesn't reflect reality. That limited view was constructed in the first place, and it can be dismantled,” said Helen Young, an Australian Medieval scholar.

The Viking world and the Islamic world intersected through both trade and travel, as Vikings enthusiasts point out, but the highlighting of artifacts such as the burial clothing studied by Larsson may be a reflection of today’s divided world rather than a truly meaningful detail about a specific Vikings-era person’s beliefs.

“People want to see Arabic there, because it resonates today with a dream of a more inclusive Europe. There’s a real desire to document that Vikings had interactions, not to mention intermarriages, with many non-Vikings,” said Paul Cobb, a professor of Islamic history at the University of Pennsylvania. “That flies in the face of the white supremacists, who see Vikings as Nordic warriors defending Europe from foreign pollution, when nothing could be further from the truth. They were one of the great international societies of the Middle Ages.”

“Everybody wants a counter-narrative for the narrative that’s been put forward by white supremacists,” said Stephennie Mulder, an associate professor of Islamic art and architecture at the University of Texas at Austin. But in this particular case, it could simply be that the family of the deceased could have purchased garments with Islamic designs purely because they liked the way they looked, and wanted to send off their loved one in something special. “It would be like, for us, buying a perfume that says ‘Paris’ on it,” said Mulder. “Baghdad was the Paris of the 10th century. It was glamorous and exciting. For a Viking, this is what Arabic must have signaled: cosmopolitanism.”

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads