[DIGEST: New York Times (1, 2, 3, 4), New England Cable News, JAMA Network, Boston Globe]

In a new study testing the brains from 202 deceased football players—ranging from high school to the NFL—87 percent tested positive for chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). CTE is a degenerative disease linked to repeated blows to the head that causes symptoms such as confusion, memory loss, depression and dementia. Symptoms often arise years after causation. Specifically, 111 of those brains studied belonged to NFL players, of which 110 had CTE.

The author of the study, Dr. Ann McKee, chief of neuropathology at the VA Boston Healthcare System and Director of the CTE Center at Boston University, has amassed the largest brain bank in the world. However, Dr. McKee warns that this particular study does not represent a random sample of NFL retirees because many families donated the brains specifically because their family members exhibited symptoms of CTE. Nonetheless, the findings provide significant scientific evidence of the risk of an NFL player developing the condition, which can be diagnosed only after death.

How CTE Is Diagnosed

McKee examined thin slices of each brain, and dyed them to highlight buildup of clusters of an abnormal protein, known as “tau,” which is the tell-tale marker for CTE. These tau clusters attack specific areas of the brain that control the symptoms that occur when people with CTE are alive. For example, Hall of Fame quarterback Ken Stabler’s brain showed clusters in the prefrontal cortex which affects working memory and executive function; the insula, which helps control social perception, self-awareness, and emotions; the amygdala, affecting anxiety, emotional control and aggression; and the mammillary bodies, which are significant for memory.

The researchers also reviewed each subject’s medical records and spoke to their living relatives about the subjects’ behavioral patterns to check for symptoms consistent with CTE.

How Football Causes CTE

The study found CTE in the brains of football players from players who died at ages 23-89 and from every position on the field—from linemen to quarterbacks, and even punters. But within the context of the study, some positions showed up more than others.

While linemen show up most frequently in the study, it’s important to remember the source of the subjects is not by random selection. Yet linemen knock heads in a violent way on every play—as much as 62 times per game according to one Stanford study. It’s likely that these repetitive blows cause CTE, more than any one concussive blow. Each one of these sub-concussive blows to the head is comparable to the effects of driving a car into a brick wall at 30 miles per hour.

In recent years, the NFL has implemented rule changes that provide quarterbacks extra protection from the hits they receive. But Ken Stabler, who played for the Oakland Raiders in the 1970s, did not benefit from those protections. Before his death in 2015 of colon cancer, Stabler requested his brain be examined to discover why he felt negative changes in his mental health. McKee diagnosed his brain with a moderate case of CTE.

Defensive Back Tyler Sash accidentally overdosed on painkillers at 27 years old in 2015 after playing football for 16 years. His family requested a CTE examination because he was demonstrating memory loss, confusion, and uncharacteristic anger.

McKee explained, “Even though he was only 27, he played 16 years of football, and we’re finding over and over that it’s the duration of exposure to football that gives you a high risk for C.T.E. Certainly, 16 years is a high exposure.”

Suicide and CTE

One fact uncovered by the study was that even those diagnosed with mild CTE showed evidence of crippling mental problems after years of playing football, such as agitation, memory loss, impulsivity, and explosive tempers.

“One of the large mysteries of this disease is why are people so affected even in the early stages,” McKee said.

While McKee and other researchers explain that no scientific correlation yet exists between suicide and CTE, numerous players with CTE died by suicide. Of the 177 cases of CTE found in McKean’s study, 18 of those deaths were suicides. According to the background research, more than half those subjects had contemplated suicide. In fact, among those diagnosed with mild CTE, suicide was the leading cause of death.

Meanwhile, current and former NFL players struggle with fears about CTE. Frank Wainright died of a heart attack caused by a brain bleed, following retirement from a 10-year career in the NFL. The last eight years of his life were haunted with fears of CTE because of confusion, memory loss and behavior changes that led him to insist on donating his brain.

"A lot of families are really tragically affected by it - not even mentioning what these men are going through and they're really not sure what is happening to them. It's like a storm that you can't quite get out of," his wife, Stacie, said.

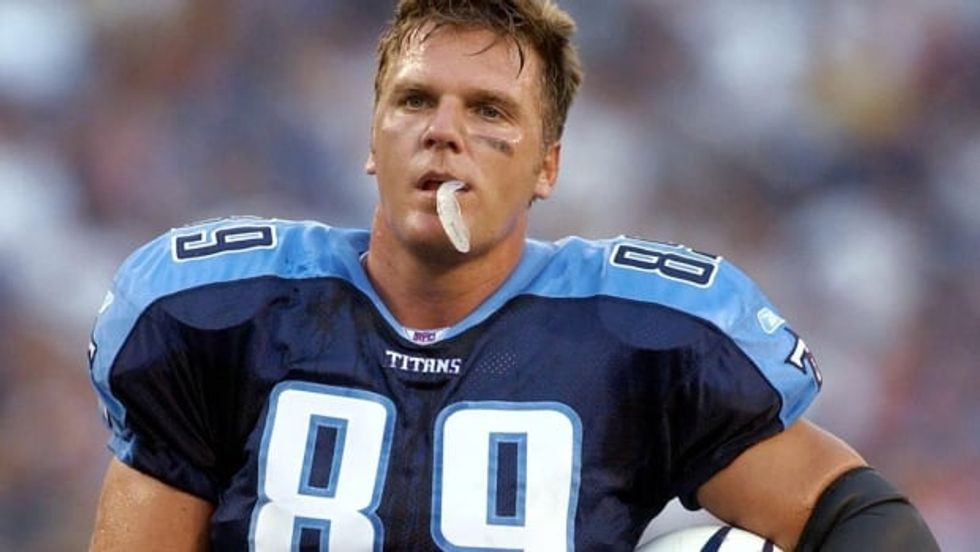

Another former NFL tight end, Frank Wychek fears that numerous concussions have left him with CTE at age 45; he also plans to donate his brain for research.

"Some people have heads made of concrete, and it doesn't really affect some of those guys," he said. "But CTE is real."

"I know I'm suffering through it, and it's been a struggle and I feel for all the guys out there that are going through this," Wycheck said.

Reaction to Study Results

Following the study, McKee said, “It’s impossible to ignore this anymore.” She added, “It’s no longer debatable whether or not there is a problem in football—there is a problem.”

Dr. David L. Brody, a neurology professor at Washington University’s School of Medicine in St. Louis, said the new study brings new solidity and depth to the scientific community’s understanding of CTE. Other studies have shown similar results, but “never on this scale, and never so systematically,” according to Brody, who had no involvement with this study but has worked on other research with McKee.

After researching CTE for years, McKee still described herself and her team as “startled” by the incredibly high prevalence of CTE within their study.

Despite calling it an “excellent study,” David A. Hovda, director of the UCLA Brain Injury Research Center, questions the ability to diagnose the condition as mild or severe by examining sections of the brain. He also questions whether examining brains from players who did not use the current safety equipment would be relevant now, as similar effects may not occur.

But McKee wants to take her research further, saying, "There are many questions that remain unanswered," said McKee. "How common is this?" she wants to know—both among football players and the general population.

Beyond those questions, she wants more answers that can lead to prevention, and eventually a cure, as there is currently no known treatment for CTE.

"How many years of football is too many?" she asks, and "What is the genetic risk?”

McKee explained that it’s also unclear to what extent some players’ lifestyle habits, such as alcohol, drugs, steroids or diet, may somehow play a role in the development of this condition.

While current research shows CTE may only be diagnosed once a patient is deceased, some researchers are already experimenting with tests performed on the living.

Ideally, the research from the brain bank would lead to an ability to detect the disease while people were alive—as McKee says, "while there's still a chance to do something about it."

What Does the Study Mean for Football?

The NFL spent years denying any link between playing football—including head blows—and brain disease before finally agreeing to a $1 billion settlement compensating former players who had filed claims against the league for hiding the risks.

Then, in March 2016—in a round table discussion on Capitol Hill—during questioning by Representative Jan Schakowsky of Illinois, NFL’s senior vice president for Health and Safety Policy Jeff Miller admitted the link between CTE and football.

“The answer to that is certainly, yes,” Miller said.

In a comment following the release of McKee’s study, the National Football League (NFL) released a statement praising the scientists’ work and emphasizing the NFL’s own dedication to research.

“The medical and scientific communities will benefit from this publication, and the NFL will continue to work with a wide range of experts to improve the health of current and former NFL athletes,” the statement said. “The NFL is committed to supporting scientific research into CTE and advancing progress in the prevention and treatment of head injuries.”

Meanwhile, NFL-backed youth programs struggle to maintain their enrollment while there is increasing public perception that football is unsafe. As a result, the number of children playing tackle football has dropped. Since 2009, the number of boys ages six to 12 fell almost 20 percent. Multiple states have shut down their schools’ tackle football programs, based on safety concerns and insufficient players.

In an effort to soothe concerns, the NFL and U.S.A. Football--the national governing body for amateur football--even misrepresented findings of a July 2015 study, exaggerating the effects of their safety measures in online materials and congressional testimony. Based on their preliminary findings, an independent research company, Datalys, reported that leagues using Heads Up Football’s safety program--a health and safety organization founded by U.S.A. football also aimed at reassuring parents--suffered 76 percent fewer injuries, 34 fewer concussions during games, and 29 percent fewer during practices. In fact, a later study revealed that only when combined with Pop Warner League safety measures did these statistics actually bear out. Otherwise, there were essentially no reductions in concussions using Head’s Up Football’s program alone, and the reduction in overall injuries was closer to 45 percent than 76 percent, as reported.

“U.S.A. Football erred in not conducting a more thorough review with Datalys to ensure that our data was up to date,” Scott Hallenbeck, executive director of U.S.A. Football, emailed The New York Times. “We regret that error.”

U.S.A. Football is now scrambling to find other options than full tackle football for young children. They now offer flag football and are rolling out a new version of tackle football with fewer players on the field to avoid player pileups, along with a smaller field and a few other changes.

“The issue is participation has dropped, and there’s concern among parents about when is the right age to start playing tackle, if at all,” said Mark Murphy, the president of the Green Bay Packers and a board member at U.S.A. Football.

“By bringing the field in, first of all, I think there’s better form tackling because less speed, less momentum, more one-on-one tackling,” according to Chuck Kyle, football coach at St. Ignatius High School in Cleveland, Ohio. “I didn’t see as many pileups, because there’s seven people” on a side, not eleven. However, he said much more work would be needed to determine if the game was, in fact, safer.

Even more skeptical were the medical experts and advocates for safe sports, who talk about the dangers to children receiving blows to the head, even from one-on-one tackles.

Terry O’Neil, the founder of Practice Like Pros—which advocates the reduction of collisions in youth football—says,“If there’s tackling, then it doesn’t matter if it’s seven on seven or one on one.” He adds, “There’s going to be contact with the other players and the ground. With the science available now, we find it surprising anyone would be promoting youth tackle football in any format.” Consistent with the findings of McKee’s study, O’Neil advocates that youth should play flag football through junior high school, thereby reducing the number of years a player receives blows to the head.

Yet even introducing modified tackle football in youth leagues on a wide scale would be a great challenge, says Jon Butler, the executive director of Pop Warner, the largest youth football organization in the country.

Despite the all the famous retired NFL players living in fear of CTE and arranging the donations of their brains to science, the parents and football coaches of children who hold tight to the tradition of tackle football on 100-yard field by 22 kids at once, may prove to be the largest obstacle standing in the way of change.

Butler explained, “We’d get a rebellion if we tried [modified football] because so many people don’t want to be told what to do.”

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads