This article is the second in a series about using technology to overcome the most primal challenges to humanity: disease, aging and death.

When I taught Introduction to Cognitive Science at the University of California, Los Angeles, I put the following thought experiment to my students: Imagine that we could study a single neuron in your brain so well that we know everything about it. We know how it reacts to signals from other neurons, we know how it responds to neurotransmitters and hormones. We know exactly how it affects the rest of your brain and body. And with that knowledge, we build a tiny artificial imitation of that one neuron, and we replace the original neuron with our imitation. Nothing is different about how your body or brain works: as far as everything else in your body is concerned, nothing has changed.

Are you still you?

Most students said “yes.” Then I continued: Now I do the same thing with another neuron, and another. Now 10% of the brain is made up of artificial neurons. Are you still you? What about at 50%? Remember, these artificial neurons are perfect replicas of the originals, so everything still functions the same. How much of the brain has to be made up of artificial neurons before you stop being you? What happens when you replace that very last biological neuron with an artificial replica?

At this point, the class usually split into two groups. On one hand, there were those who, following the logic of the thought experiment, decided that the substance of the neurons didn’t matter. At a fundamental and even molecular level, both biological and artificial neurons were basically just complicated little gadgets. As long as the parts do the same things, it doesn’t matter if they are made of biological molecules or molecules of silicon and plastic.

On the other hand, some students were uncomfortable with the idea that an artificial neuron could ever truly replace a biological neuron, no matter how complex and detailed the replica might be. How do we know it’s possible for an artificial neuron to do everything the biological neuron does? When we build our replicas, how do we know we didn’t miss anything? In every class, there were at least some students who had the strong intuition that there must be something about the biological neuron that could not be replaced by an artificial counterpart.

This divide, which showed up in the classroom every time I taught this course, reflects a deep philosophical split that divides people across this country, and across the world, even though we rarely talk about it.

Out of the Classroom, Into the Lab

Until now, this was merely hypothetical, and has only recently come up as a practical question. The first article in this series talked about some of the rapid technological innovations that are paving the way for this thought experiment to become a reality. Ambitious projects like the 2045 Initiative are already laying out roadmaps to the

future by spelling out exactly what we need to accomplish, technologically-speaking, for our conscious selves to exist apart from biological bodies or brains.

The goal has obvious appeal. In theory, people could live as long as they want. They wouldn’t need to worry specifically about biological disease. Sure, there would still be problems. Even highly advanced technological bodies are likely to have their own issues, whether it is interference or wear-and-tear; but wouldn’t it be nice to no longer have to worry about the deadly effects of Alzheimer's, cancer or even the common cold?

The motivation of the 2045 Initiative isn’t where people usually get stuck. Like the students in my class who had reservations about the “artificial brain” thought-experiment, their concern goes straight to the foundations of the idea: Why do scientists think this is possible in the first place?

The Soft Machine

“Imagine you’re a machine. Yes, I know. But imagine you are a different kind of machine, one built from metal and plastic and designed not by blind, haphazard natural selection but by engineers and astrophysicists with their gaze fixed firmly on specific goals.” -- Peter Watts, Blindsight

Most scientists who study the mind believe that the human body in general, and the brain in particular, is a type of machine. A brain is a machine that takes in information, stores it and transforms it, and produces output that then drives the body. This is sometimes called the “computational view” of the mind, because according to this view, your consciousness is simply the “software” or program that is being run on the hardware (or perhaps more accurately, the “wetware”) of your brain.

This is not a metaphor. Rather, this is important to emphasize, because many non-scientists misunderstand this. It would be a metaphor to compare your brain to a laptop or desktop computer, of course. But to cognitive scientists, “computer” is a general term that applies to any device that takes in information, transforms it, and produces output. Your laptop is one of these, but so is your brain.

That is why so many scientists and academics believe that the eventual goal of getting a human mind into an artificial computer is not only possible, but in a basic

philosophical sense, unremarkable. Of course you can upload your consciousness to a machine, because you already are a machine.

This attitude is so ingrained in cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and artificial intelligence that researchers in those fields don’t even question it. Unfortunately, that is also why they rarely take the time to explain it. As a result, what we see in the popular press and across the internet is a split: those people for whom the idea of “running” a human mind on an artificial brain is obvious, and those for whom it is absurd fantasy.

To better understand why so many scientists take it for granted that our consciousness--the very essence of self--can be uploaded to computers, it is useful to look how the idea came about in the first place.

A Brief History of the Science of Mind

“It doesn’t matter what the actual physical situation is, a curve is ever a curve… we are free from all that old nonsense now! Meaning the Aristotelian approach… All that mattered henceforth, was what form they adopted when translated into the language of analysis.” -- Neal Stephenson, Quicksilver

This quote is a fictional account of a conversation between Isaac Newton and a friend in 1665, where Newton is trying to convey the philosophical importance of his theory of fluxion: an idea that today we call calculus.

The fictional Isaac Newton goes on to explain: “Translating a thing into the analytical language is akin to what the alchemist does when he extracts, from some crude ore, a pure spirit, or virtue, or pneuma… And when this is done we may learn that some things that are superficially different are, in their real nature, the same.”

Although this is a fictional account, it captures a pivotal moment in the history of scientific thinking. Prior to the scientific revolution of the 17th century, most philosophers held the traditional essentialist view advocated by Aristotle: an object is what it is because of its essence. Because human beings and machines are made up of different things, it is common sense that they are different things!

But the scientific revolution of the 1600s began to turn this kind of thinking on its head. Scientists had made such extraordinary breakthroughs in physics, mathematics and chemistry merely by applying logical and mathematical analysis, that philosophers from all branches of thought were eager to see exactly how far this kind of thinking could go. What can we discover if we look not at what things are made of, but how they function: their mathematical and logical relationships, their causes and effects?

Not everyone was willing to make the full jump to viewing the human mind as a type of machine, of course. René Descartes walked right up to the edge of talking about the human mind as a machine, but shied away at the last minute. He dissected animals and studied human cadavers, and came to the conclusion that animals and plants, and

even the human body, are all machines. To Descartes, this meant simply that they are physical objects made up of complex interconnected parts that follow the laws of cause and effect.

However, he then postulated that human beings must have something extra. Human beings, Descartes proposed, are unique in that they also have a mental existence, by virtue of their having a soul, that no non-humans have. This gave rise to the “mind-body dualism” that has been a popular view in the philosophy of mind ever since.

It was another half century before Julien Offray de La Mettrie, in 1748, first took the plunge with his book L'homme Machine (“Man, a machine”). He looks at Descartes’s argument, admires it, and concludes that Descartes was almost completely right… except that there is no real reason to postulate the “something extra” of the mind. Instead, he argued that the mind is merely the complex functioning of an incredibly intricate machine: the brain.

It took a couple of hundred years, however, for neuroscience to catch up with that idea, and decode what the brain actually does. In 1906, Camillo Golgi and Santiago Ramón y Cajal won the Nobel Prize for their contribution to the “neuron doctrine”: the understanding that the entire complex functioning of the brain could be understood as the interaction between basic cells called “neurons.” It isn’t magical or mysterious: it is rule-based cause and effect. Just like any other machine.

In 1943, Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts published a paper called “A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity,” which examined neurons from a functional and mathematical perspective. Looking at new theories that were springing up about computation and computers, they concluded that the signals and interactions between neurons could be understood as computing logical functions. The activation of neurons in the brain could therefore be understood as the physical phenomenon underlying the activation of memories, thoughts, and ideas. Finally, there was a theory that drew a solid connection between the physical mechanics of brain activity, and this nebulous thing we call “consciousness.”

These discoveries revolutionized the way we think about the mind as well. That same decade, anthropologist Gregory Bateson argued that a blind man using a stick to “feel” the ground in front of him is essentially using the stick the same way that you or I might use our hands to feel a wall or an object. From a purely functional point of view, there is no difference between the stick and a neuron: both are transmitting signals from a remote place “out there” to your brain. Bateson concluded that any time you use

technology to sense “the world,” the line between you and the technology blurs: the technology becomes part of your self, just like your arm or your eye.

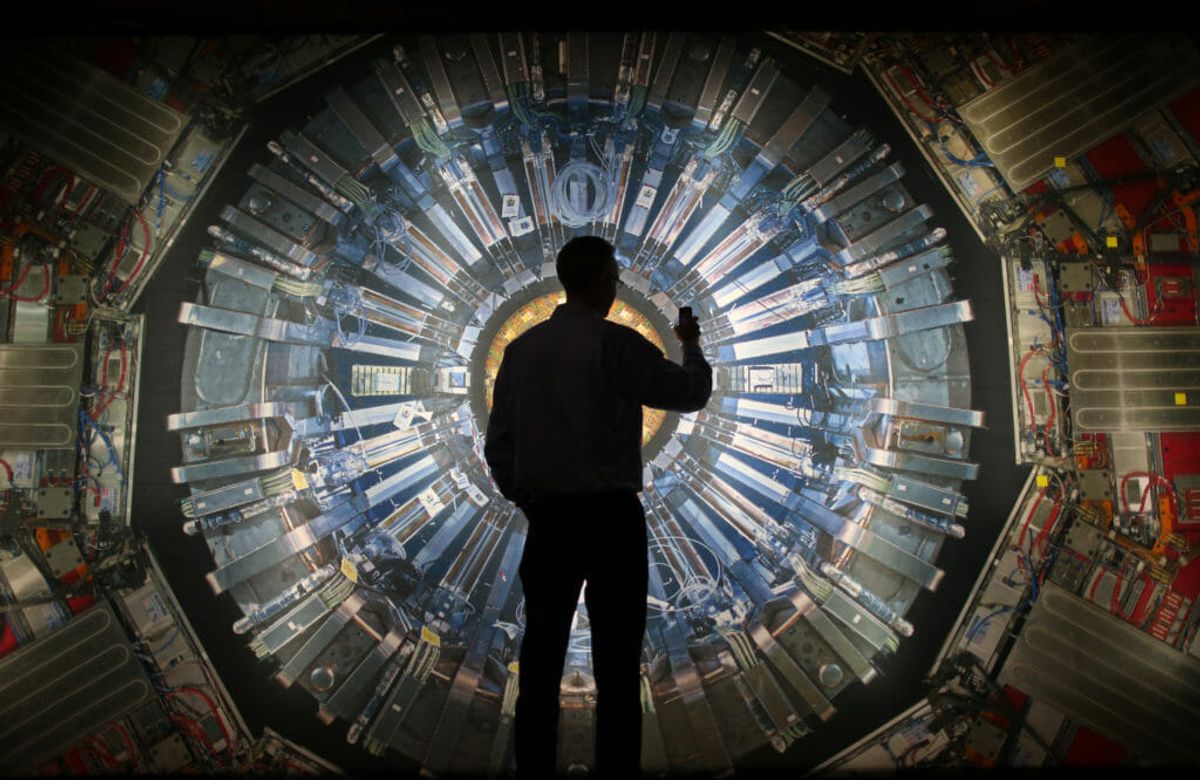

This idea has been rediscovered today by the transhumanists. Just recently, techno-philosopher Jason Silva observed that your cell phone is really a type of mind upgrade. Transfer our minds to machines? If our sensory systems are machines for transmitting signals from the world to our brains, then we are already part-way there. When you understand the idea of “mind” and “self” from a scientific perspective, we are already cyborgs.

The Ghost in the Shell

Science and technology are advancing, and the rest of society is being dragged along with it. This scares some people, but it needn’t. A while back, I interviewed several theologians about the implications of the transhumanist agenda of transferring our minds into mechanical bodies. None of them was particularly bothered by it.

In fact, people who study theology as a career have engaged in complex and sophisticated debates about the relationship between the body and the soul for a very long time. To them, the advance of technology and potential that we might be able to test the idea of uploading consciousness represents a great opportunity for growth in theology as well as science.

Consider the popular religious quotation, “You don’t have a soul. You are a soul; you have a body.” It could be viewed as the perfect expression of the computational view of the mind. You are the software, the program. It is the “information processing” that defines who you are. The hardware that the program happens to be running on, your body, isn’t what matters.

Of course, there will always still be skeptics: people who believe that artificial “replica” neurons could not possibly capture everything important that biological neurons do. But our technology will soon be advanced enough that we can put this long-running theory to the ultimate test.

It may not happen by 2045, but some time before the current generation of Millennials has reached old age, we will have a scientific answer to the question: is a human mind software that can be run any machine, as long as it has the right information-processing capabilities?

If it doesn’t work, it won’t be the first time a long-standing scientific theory is proven false. If it does work, on the other hand, it will be time to start asking another question: now that we know conscious, thinking human beings can exist inside non-aging, infinitely-repairable artificial bodies... what happens next?

In the third article in this series, I will interview three prominent transhumanists and supporters of the 2045 Initiative, to discuss the upheaval that successfully transferring our consciousness into artificial bodies could cause society.

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads