[DIGEST: Science Alert, Salk Institute, Science Daily, Science, Wikipedia, Medical Xpress]

For the first time, scientists have been able to successfully reverse signs of aging in a live animal through cellular reprogramming.

While the particular process, which involves the introduction of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), is not new, prior attempts at cellular reprogramming in mice resulted in death either immediately from organ failure or eventually from uncontrolled tumor growth.

Stem cells are especially important in aging and genetic research because of their unique ability to regenerate into many types of cell in the body. Pluripotent stem cells are even more remarkable because of their versatility—unlike multipotent stem cells, which can become just a couple different cell types, pluripotent stem cells can become anything, including blood, nerves, and skin.

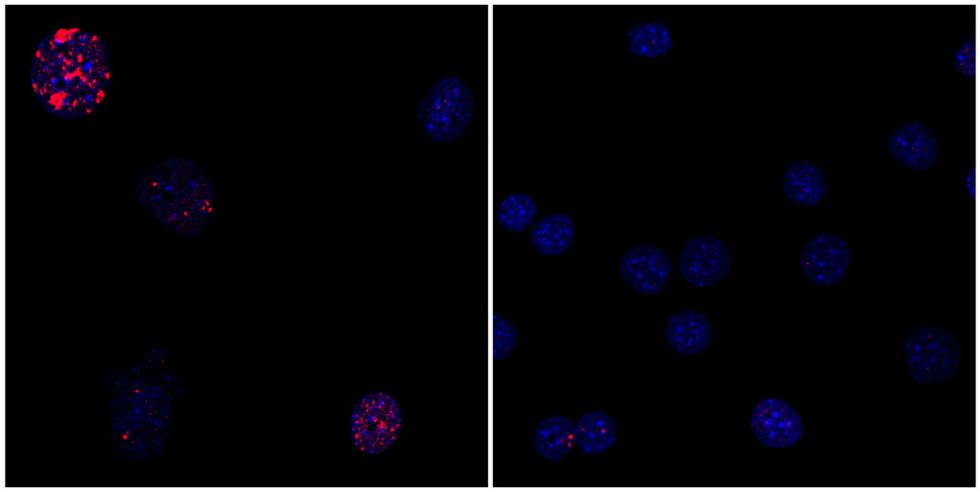

Traditional cellular reprogramming involves switching on key genes in cells for two to three weeks, the typical amount of time required for a cell to reach pluripotency. A team of researchers at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California, however, found that by reducing this period to two to four days, the cells did not become fully pluripotent—a skin cell remained a skin cell, for example. Scientists discovered that with this new shortened period, they were able to avoid the high rate of premature death and tumors present in past attempts.

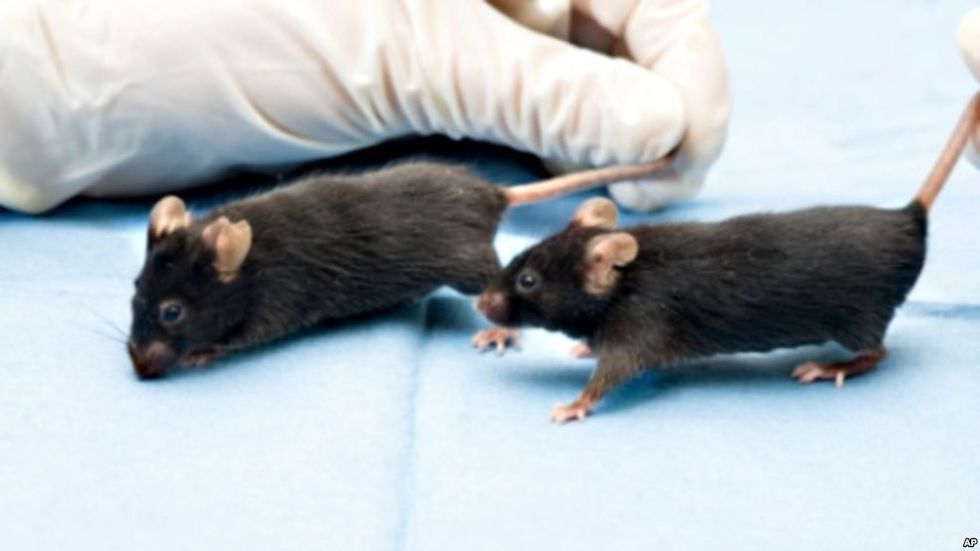

This process not only saw harvested human skin cells looking and behaving years younger, it also resulted in an increased lifespan of up to 30 percent in mice with a premature aging disease.

"We did not correct the mutation that causes premature aging in these mice," says Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, a professor in the Salk Institute's Gene Expression Laboratory and lead author of the paper detailing the findings. "We altered aging by changing the epigenome, suggesting that aging is a plastic process."

The researchers used mice with progeria, a rare disorder in both humans and animals that results in both internal and external premature aging; most people born with progeria begin to look elderly as children and ultimately die while still in their teens.

Mice with progeria that received a partial cellular reprogramming treatment lived for about 24 weeks, while the control group only lived about 18 weeks.

“We were surprised and excited to see that we were able to prolong the lifespan by in vivo [inside a living organism] reprogramming,"says Pradeep Reddy, co-author of the Salk Institute study.

The researchers were also able to regenerate injured pancreatic and muscle tissue in mice through partial reprogramming, indicating further potential for the process beyond aging reversal.

Whether or not cellular reprogramming could ever work in humans, however, remains to be seen. Due to the complexity of the human body and the course of aging in general, the Salk researchers say it could take up to 10 years just to reach the clinical trial stage.

"Obviously, mice are not humans and we know it will be much more complex to rejuvenate a person," says Izpisua Belmonte. "But this study shows that aging is a very dynamic … process, and therefore will be more amenable to therapeutic interventions than what we previously thought.”

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads