This tiny island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean might seem inviting to the casual outsider. But Nauru, barely a dot on the map measuring just eight square miles, is home to a refugee processing center backed by the Australian government. The center has been likened to a prison and cited for numerous human rights abuses. A number of detainees are children.

Disagreements among members of the European Union have strained relations between countries, and have raised questions about how to distribute limited resources as the continent faces its worst migrant crisis since World War II. Australia’s controversial policies have been widely criticized as inhumane. The plight of refugees and asylum seekers, intercepted by the boatload and placed in detention centers on poor Pacific island nations, has been compared to the struggles of the country's indigenous population. Yet the government says that stopping boats has helped to “return integrity to Australia's humanitarian and refugee program.”

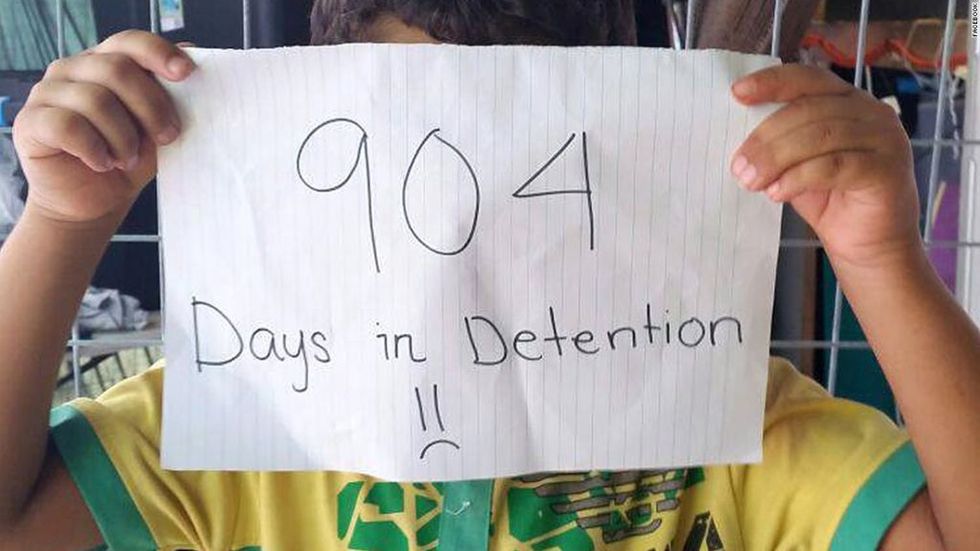

This integrity has been refuted by the testimony of children currently detained in Nauru, many of whom, in an effort to avoid potential retribution, agreed to speak with journalists on condition of anonymity. A national inquiry into immigration detention found that children detained on Nauru suffer from “extreme levels of physical, emotional, psychological and developmental distress” in an environment where sexual assault, rape and child abuse is an omnipresent threat. Families in Nauru endure sweltering heat year round in tents without air conditioning, and share their living quarters with rats and cockroaches. “We can't sleep at night because of the cockroaches,” says 12-year-old Mizba Ahmed, who has spent 18 months in detention with her family since fleeing persecution in Myanmar.

The young girl once dreamed of becoming a doctor, but has found receiving an education nearly impossible since the Australian government shut down the sole school in the refugee camp. For many children, the school was a safe space; the same cannot be said of the public school in Nauru, which both the Australian and Nauru governments have urged child detainees to attend. The children speak of prolonged harassment by other students. In one case, a 15-year

-old girl was forced to lock herself in a bathroom to escape unwanted advances from a male student. She is one of many who have stopped going to school. With nothing to do all day, boredom and depression are common among the children. “I wanted to become something,” says Mizba, “and here I am doing nothing.”

Seeing the detention center firsthand is difficult for journalists. The Nauru government offers non-refundable visa applications to the media; just one application can set a journalist back $8000, or about $5800 USD. Journalists who wish to visit Australian detention centers must first sign forms, promising they will not interview the detainees. Any content they collect must be submitted to the government for screening.

One of the most vocal advocates for shutting down the camp entirely is Australian Senator Sarah Hanson Young, who believes that the Australian government cannot justify the existence of Nauru. Young has lambasted her countrymen for not only keeping people detained there, but for failing to guarantee the safety of entire families, including women and children. “There is very, very little information let out of the camp,” she says, “and staff who work at the center are essentially gagged.” Indeed, obtaining information about the conditions within the camp has been difficult; current and former camp residents had to be interviewed remotely.

The Australian government has assumed no responsibility for the lack of access. Instead, they defer all inquiries to the Nauru government. The Nauru government, in turn, has maintained its tight restrictions on all foreigners, at more than one juncture barring access to representatives with Amnesty International. In 2014, the organizationcould not investigate reports that children and their families were being housed in an area where an unexploded artillery shell was discovered. Nor could they probe allegations that children at the center were being assaulted by guards. The Nauru government declined

the organization's requests despite repeated attempts to set up alternative dates. Rupert Abbott, Amnesty International's Deputy Asia Pacific Director, called Nauru's refusal to allow independent review “another damning development in Australia's offshore asylum processing system.”

The conditions in Nauru are the latest in a string of human rights violations stemming from Australia's history of discriminatory immigration policies and brutal treatment of Indigenous Australians. Immigration to Australia was restricted almost exclusively to whites until the 1970s, giving preferential treatment to the British under what was known as The White Australia Policy. In the late 19th century, Australia's Aborigines were sometimes hunted like animals and imprisoned for minor offenses. In fact, the disproportionate rate of

incarcerated Indigenous Australians continues today.

Similarly, the inhabitants of Nauru are “always being watched,”according to one teenager, who says that his life “doesn't mean anything inside detention.” Many detainees hail from hotbeds of conflict, having escaped the horrors of wars that decimated an area stretching from Iran and Afghanistan to Iraq and to Syria. As the current “other,” they are the unfortunate victims of policies designed to deny them any hope of settling in Australia.

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads