[DIGEST: NPR, The Washington Post]

When scientists first started sequencing the genomes of bacteria, they were astonished to find how complex and different the bacteria’s DNA were. When, in 2010, they started to create living bacteria from scratch, they found that even very small missteps could result in failure. Now, after years of trial and error, geneticists at the J. Craig Venter Institute have created a “minimal genome”: a cell with the fewest genes of all known living organisms.

(CREDIT: Source.)

(CREDIT: Source.)

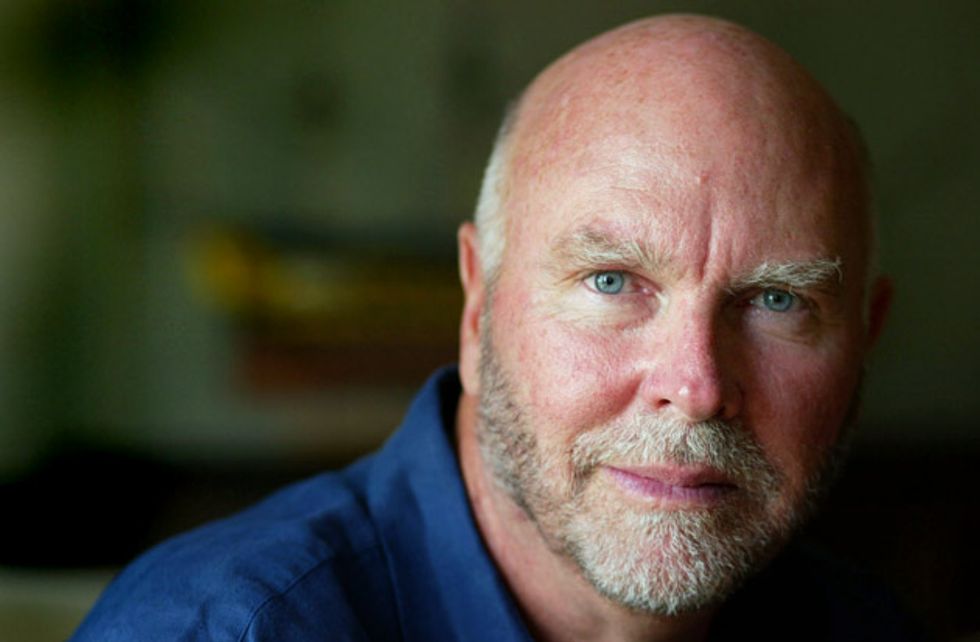

From the genesis of this long project, J. Craig Venter explained, "We were asking basic fundamental questions of life. What did we think might comprise the most primitive cell? What would be the gene content of this thing?" Venter and his team placed an extremely simple parasitic bacteria in its ideal environment and started removing genes. They discarded anything nonessential to the bacteria’s continued life and growth, until only about half of the original genome remained.

In the March 2016 issue of Science, Venter and his team describe the design and production process of their living single-cell organism with only 473 genes. No living, reproducing organism has fewer genes than this synthetic cell with the catchy name of JCVI-Syn3.0, although scientists believe that it is theoretically possible. In contrast, an individual human genome has about 20,000 genes; a sea sponge has over 18,000 genes; even an E. coli bacterium has over 4,000 genes.

Even with only 473 genes to sift through, scientists still don’t know the purpose of a third of the tiny organism’s genome: they only know that, without those 149 extra genes, the cell would not survive. Many other organisms, including humans, have comparable chunks of mystery DNA, so studying the more manageable section of DNA with unknown functions in this single-cell organism could help geneticists understand what all those genes do and why they’re so essential.

"If we can't understand what happens in a cell with less than 500 genes, imagine how

complicated it's going to be to understand our 20,000-some genes in the human genome," Venter said. "So, it's essential for understanding all of life to understand the basic components."

A growing understanding of how life works, while useful, isn’t this cell’s only potential contribution to science. The other long-term goal of this project is to engineer bespoke synthetic organisms for a variety of purposes. Dan Gibson, a synthetic biologist with the Venter Institute who worked on this project, explained, “We believe that these cells would be a very useful chassis for many industrial applications, from medicine to biochemicals, biofuels, nutrition and agriculture.”

Daniel Gibson. (Credit: Source.)

Daniel Gibson. (Credit: Source.)

With fewer genes to manipulate, scientists could more easily create cells which could consume or produce specific chemicals. The future could be full of tailored cells cleaning up the environment, producing pharmaceutical chemicals and providing fuel. Someday, doctors could synthesize vaccines on demand, farmers could design bacteria that would benefit their specific crops and livestock, and astrobiologists could create copies of organisms from other worlds.

For now, though, those exciting advances are still science fiction. As Venter said, with this simple and small living cell, "We're just trying to understand the basic components of life."

“Just,” indeed.

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads