It was a cheeky display of nationalism in the usually staid world of diplomacy.

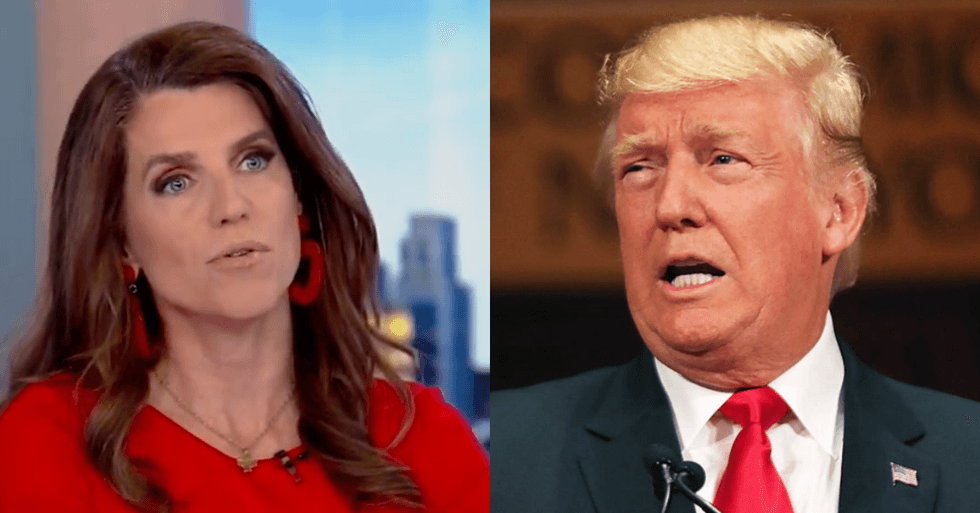

After President Donald Trump pulled the United States out of the Paris Climate Accord in June, French President Emmanuel Macron created a research fund and video designed to lure the best and brightest American climate scientists and clean technology experts to Europe. In a twist on Trump’s campaign slogan, Macron even launched a comprehensive website and dubbed it “Make Our Planet Great Again!”

Three months in, many might be wondering how well the program is working. In a word, famously.

Hundreds of climate scientists — including 75 Americans — have applied to work in a collegial and supportive country that has created a $70 million fund for new climate research. Some are looking to do six-month, or year-long projects, but others are looking to stay for years. France’s reputation as a scientist-loving country has been burnished until it shines.

Ashley Ballantyne is among the hopefuls. Ballantyne, a bioclimatologist at the University of Montana in Missoula, wants to built a global carbon-observing network that fuses satellite and atmospheric data to better understand how ecosystems react to a rapidly changing climate. "There are very few funding opportunities in the United States that promote research on carbon–climate interactions at the global scale,” he says, “so the fact this program was looking for visionary thinking was appealing.”

Germany has been so impressed with France’s results that they have launched their own initiative valued at $35 million.

It couldn’t come at a worse time for the United States. Climate change experts are needed, even if just to lend their voices to champion a cause that should be beyond debate. Hurricane Harvey and Irma have devastated huge swathes of Houston, Louisiana, and Florida, so Americans are relying on climate science more than ever. Even conservative Republicans — only 15 percent of whom believe that humans are causing climate change — must be wondering why the US suffered two 500-year storms in the space of two weeks.

But who could blame scientists for looking elsewhere to advance their careers? With the White House and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) both fighting hard against climate science at every turn, many of the best and brightest minds in America know the only way to find worthy solutions to the climate crisis is to go elsewhere.

Climate scientists in America have endured a miserable eight months. Soon after all mention of climate change was removed from government websites after inauguration, the White House proffered a budget that cut the EPA off at the knees, and defunded climate science at NASA. It didn’t pass, but the September proposal is just as devastating. EPA administrator Scott Pruitt has been jettisoning scientists left and right. In June, the US became the only country to withdraw from the Paris Accord.

Climate scientists understood the message as clearly as if it had been delivered with skywriting.

In truth, it’s never been easy to be a climate scientist in the USA. Big Oil has always carried a bigger stick in Congress, and most of the recent advances in limiting greenhouse gas emissions have come through a series of executive orders by President Barack Obama who wanted to leave a lasting environmental legacy.

That legacy is now in jeopardy. But, as many pundits point out, the US can’t officially withdraw from the Paris Accord until after the next election. It could still be stopped. But if it isn’t, more than a few American PhDs might be speaking French like a native.

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads