One of the most basic and essential banking services—and the gateway to establishing credit—may now be a privilege only for the well-to-do, or at least the financially stable and predictable. Need to pay for basics, like housing and utilities, with a check? You may pay more to do so than your higher-earning neighbors.

In January, Bank of America announced the end of its Free Checking service. The bank was one of the largest, and only remaining, brick-and-mortar banks to offer this service. Existing customers are now funneled into the bank’s Core Checking program, an option that requires customers to keep a minimum daily balance of $1,500 or make at least one direct deposit a month of $250 or more. If your balance dips below that point, you’ll be charged $12 a month. In other words, if you don’t have enough money to meet those qualifications, get ready to get more broke.

How hard is it to keep a steady balance above $1,500? A Bankrate survey of American households found that only 39 percent of respondents would be able to cover a $1,000 setback using their savings. A survey from the National Endowment for Financial Education found that 45 percent of U.S. adults are living paycheck to paycheck.

Bank of America, meanwhile, is doing just fine. The company is expected to reap a multi-billion windfall as a result of the recent federal tax overhaul.

"It is difficult to understand why one of America's largest banks would end a program that many low-income families rely on just weeks after benefitting from one of the largest tax cuts in American history," said Reps. Elijah Cummings and Jimmy Gomez, two members of Congress who serve on the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. "Surely, your corporation could have devoted at least a fraction of these massive savings to maintaining existing programs that help low-income families move towards financial security and independence rather than forcing them to turn to alternative financial services providers," the letter added.

A Bankrate.com study found that Americans with an annual household income under $30,000 pay more than three times the monthly bank fees paid by higher-income brackets—an average of $31 a month, compared with an average of $9 for other income groups. The same study found that just 41 percent of Americans with incomes under $30,000 have a checking account.

"The debate over Bank of America's accounts and fees points to a larger economic justice issue—people with less income pay more to get cash, make payments, and conduct their business," said Dory Rand, president of the Woodstock Institute. "Without access to safe and affordable bank accounts, low-income consumers often turn to costly alternative financial services, such as currency exchanges or check-cashers.”

A free checking account has long been a rite of passage for young people’s first banking experience. As their income grows, they can opt for more “fully featured” banking experiences, but for those who live close to the edge, predatory banking practices may push them over the edge. The people most likely to be affected include students, seasonal workers, freelancers and people of color.

Whites-Only Banking

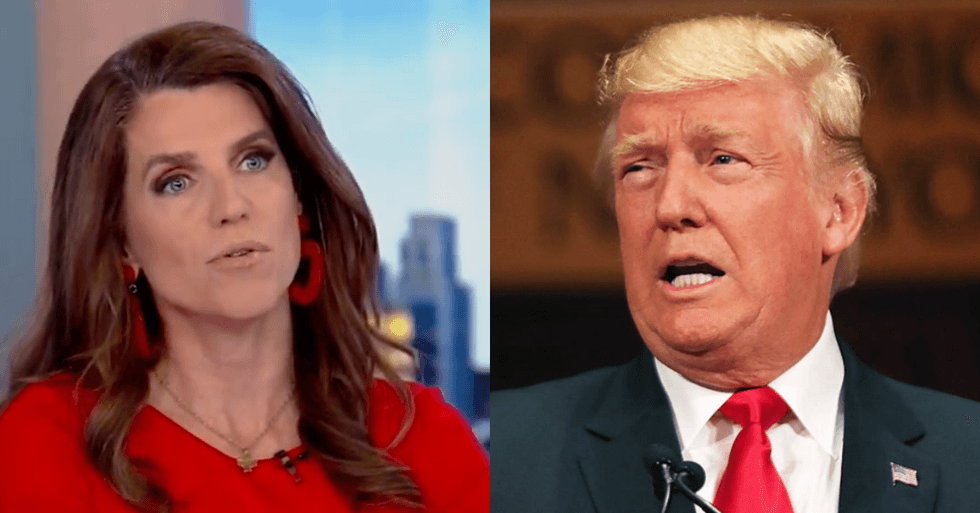

The end of free checking—at Bank of America and smaller banks across the country— is part of a wider trend to disenfranchise people of color from financial products that has taken hold since Trump took office. The gutting of anti-discrimination measures across the financial services sector, including mortgages, car loans, and payday loans, is being pushed by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), which was created in the wake of the 2007 financial crisis to prevent Americans from getting ripped off by financial firms, but is now operating under new objectives under Trump.

“This is a pattern we have observed, and it’s fairly alarming,” says Yana Miles, senior legislative counsel at the Center for Responsible Lending. “You have good policy that protects consumers and tries to address discrimination. We’re seeing these rules delayed, picked at, or invalidated.”

Other examples: Trump’s Department of Housing and Urban Development will delay enforcement of an Obama-era rule that requires local governments to identify racial segregation in housing and develop plans to address it. The CFPB, now run by Mick Mulvaney, is looking to repeal landmark federal restrictions on payday lenders, who target communities of color when setting up locations and engage in banking practices such as loans with rates as high as 950 percent. The CFPB has also announced it would strip enforcement powers from the Office of Fair Lending and Equal Opportunity, the agency’s division responsible for protecting minority borrowers against discriminatory lending. In 2013, under Obama, the CFPB targeted car dealers who charged higher interest rates on nonwhite customers; under Mulvaney, those practices are now A-OK again.

In particular, African Americans are denied home loans at disproportionate rates, even when factors such as income, savings, educational level and profession are the same or better than that of white applicants. The repeal or limited enforcement of anti-discrimination legislation contributes to a homeownership gap between whites and African Americans that is now wider during the Jim Crow era.

"Wealth and financial stability are inextricably linked to housing opportunity and homeownership," said Lisa Rice, executive vice president of the National Fair Housing Alliance. "For a typical family, the largest share of their wealth emanates from homeownership and home equity."

The U.S. Census Bureau shows the median net worth for an African-American family is now $9,000, compared with $132,000 for a white family—in large part due to lower levels of homeownership. A policy of discrimination against issuing mortgages to people of color, known as redlining, creates segregated communities and pushes longtime residents from communities that are targeted for gentrification. The problem is likely to deepen as regulations on discriminatory and predatory banking practices continue to relax: During President Donald Trump’s first year in office, the Justice Department did not sue a single lender for racial discrimination.

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads