On April 12, the United States recognized Equal Pay Day. This was more an aspiration than reality, as even in 2015, female full-time workers made 79 cents for every dollar earned by men. That discrepancy increases when the woman has children. According to 2013 data, mothers employed full time are paid 71 cents for every dollar paid to fathers. This gap is even worse for single mothers with full-time jobs, who are paid 58 cents for every dollar paid to fathers. (In contrast, a recent study found fathers with one child earned 21 percent more than childless men.)

But what about women who don’t have kids? Are they subject to the same discrimination?

According to some, yes.

Pregnant Women Held to a Higher Standard, But Earn Less

Pregnant women face a wage penalty, as well as more insidious prejudice. A 2007 article in American Journal of Sociology by Shelley Correll and others found that “visibly pregnant women are judged as less committed to their jobs, less dependable, and less authoritative, but warmer, more emotional, and more irrational than otherwise equal women managers who are not visibly pregnant.”

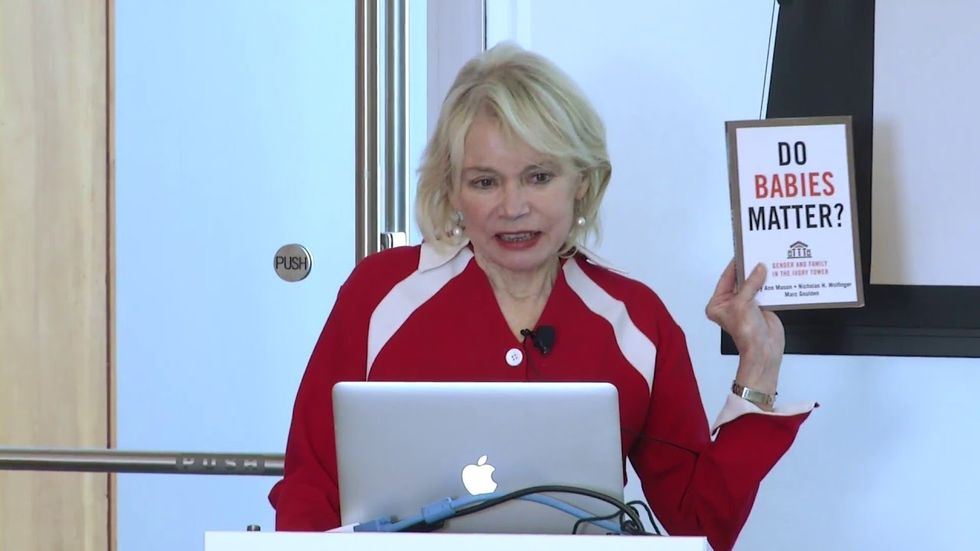

Shelley Correll. (Credit: Source.)

Shelley Correll. (Credit: Source.)

In a 2007 Harvard Business Review paper, Will Working Mothers Take Your Company to Court, researchers found that opportunities for advancement are denied to pregnant women, sometimes in order to make a point about where the female worker’s priorities should lie. The paper describes a woman who was denied a prestigious fellowship because

her boss “didn’t want to reward her for her personal decisions (and implicitly support them). He didn’t want her as a representative of success.”

This sort of discrimination is not uncommon. In 2006, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission received nearly 5,000 complaints of pregnancy-based discrimination, up 30 percent from the previous decade. In 2010, more than 6,000 complaints were filed. Yet, “[t]here are many more women discriminated against in the workplace due to pregnancy, family, and gender than will ever come forward to file a claim,” said Diane King, a Colorado employment attorney.

The pregnancy penalty is particularly grim in certain industries, such as academia. Female graduate students who are pregnant or have young children are 132 percent more likely to be working in an untenured, adjunct or temporary academia job than a man with a young child.

Science-related fields are also particularly brutal for women of child-bearing age. “In fields like science, scientists are very nervous about having pregnant women because science is a big competition. You have to get there first. If you feel you have someone that is not going to be a hundred percent hitter, you are not going to keep them up front,” said Mary Ann Mason, professor and co-director of the Center for Economic & Family Security at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law.

But pregnant women don’t need studies to drive this point home, said Katherine Zaleski, cofounder and president of PowertoFly, an organization that connects women with

jobs that support work-life balance. “A lot of women feel like, if they don’t keep [their pregnancy] under wraps, they’re going to get taken off projects that they’d been spending months, if not years working towards.”

The “Undependable” Pregnant Woman

The notion that a pregnant woman is not a “hundred percent hitter” is deeply engrained in our society. “Pregnant women and mothers are assumed to be less committed to their careers, and every time they leave the office or ask for any flexibility, that commitment is further called into question,” said Anne-Marie Slaughter, former director of policy planning for the U.S. State Department.

An analysis of sex-based discrimination cases from the Ohio Civil Rights Commission between 1986 and 2003 provided further evidence of the pervasiveness of this notion. Researchers Reginald A. Byron and Vincent J. Roscigno found that “cultural stereotypes and statistical discrimination are an important part of the inequality that pregnant women experience.” Employers often viewed pregnant workers as undependable and failed to hold them to the same standards as other workers.

“This kind of discrimination is institutionalized,” agreed Lisa Maatz, a policy adviser with the American Association of University Women. “It’s a part of the culture, it’s a part of the decision-making process. Right now the assumptions about women’s roles, as stereotypical as they may be, are driving decisions and those decisions disadvantage women.”

The Pre-Pregnancy Penalty?

The penalty can start even earlier than pregnancy. The mere possibility that a woman will become pregnant someday can lead employers to pass women of childbearing age over for promotions, or not hire them at all.

A 2014 study by British law firm Slater & Gordon found that more than 40 percent of 500 managers surveyed were wary of hiring a woman of childbearing age, citing their fear of

maternity leave and a belief that they would not be as good at their jobs when they returned from leave.

Despite the candid British study, a pre-pregnancy penalty is difficult to measure, in part because under United States law, employers cannot officially base employment decisions on pregnancy or future pregnancies. Rather than risk a lawsuit by asking about a woman’s plans for the future, potential employers may turn to their male counterparts to fill spots. Said Carrie Lukas, managing director of the Independent Women’s Forum, “for young women who don’t see motherhood in their future, or have plans for parenting that don’t include stepping back from their jobs at all, the taboo against these discussions can be particularly costly.”

As the age at which children can safely bear children continues to expand, the prognosis for women of childbearing age becomes increasingly dire. Heidi Hartmann, president of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, noted that “A pregnancy penalty doesn’t just hurt mothers or expectant women, married women or even childbearing women, it’s a bias that’s applied to all women.”

Hartmann continued, “Nowadays employers probably don’t think they’re safe until that woman is [around] 49, but even then I don’t know.”

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads