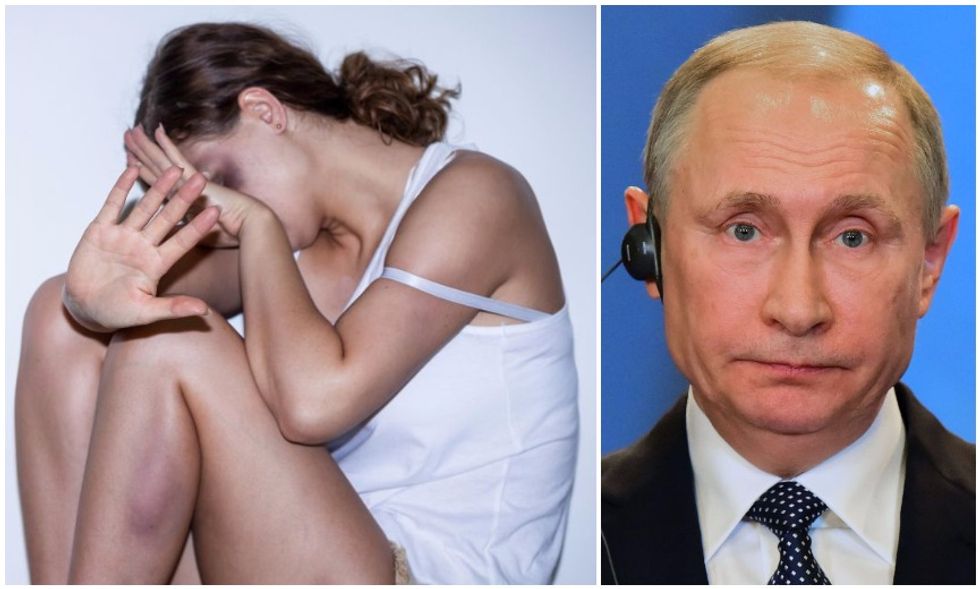

Late last month, Russian lawmakers decriminalized some forms of domestic assault. The amendment to the criminal code was passed 380 to 3 by Russia’s lower house and rubber-stamped by the upper house. President Vladimir Putin signed the amendment into law on February 7.

Under the law, if the victim—adult or child—is not “seriously” physically injured, and there has been no other incident of violence within the past year, the abuser will be subject to a maximum prison sentence of 15 days, community service, or only a fine. Prior to the amendment, the assailant would have been subject to a maximum sentence of two years.

Domestic Violence Supports “Traditional Family Values,” Proponents Successfully Argued

Domestic violence was a crime in Russia for a total of six months.

In June 2016, the Russian government decriminalized battery, but exempted domestic abuse from the decriminalization. This was the first acknowledgement of domestic violence as a specific crime. Prior to this, domestic violence was subsumed within other forms of assault.

But in carving out domestic violence as a specific offense, the Russian Supreme Court invoked the wrath of conservative groups.

In particular, the Russian Orthodox Church was furious, viewing “the reasonable and loving use of physical punishment as an essential part of the rights given to parents by God himself.”

Conservative lawmakers agreed, and quickly moved against the Supreme Court on the basis of “traditional family values.”

Yelena Mizulina, who helps make up the 13 percent of female legislators in Russia’s parliament, drafted the controversial law. Mizulina was also the driving force behind the Russian law banning “gay propaganda,” which made it illegal to equate straight and gay relationships and distribute gay rights materials.

Mizulina told parliament that “in Russian traditional families, the relationship between parents and their children is built on authority and power.” She continued that “You don’t want people to be imprisoned for two years and labeled a criminal for the rest of their lives for a slap.”

“I don’t think that we should violate the rights of family, and sometimes a man and a woman, wife and a husband, have a conflict,” said Vitaly Milonov, a member of the Russian Duma, Russia’s lower’s legislative body. “Sometimes in this conflict they use, I don’t know, a frying pan, uncooked spaghetti, and so on. Frankly speaking what we call home violence is not home violence—it’s sort of a new picture of family relations created by liberal media.”

Svetlana G. Aivazova, a Russian specialist in gender studies, sees it differently. “This [law] shows that Duma deputies are not simply conservative or traditional, it shows that they are archaic.”

A Culture of Victim Blaming

As the famous Russian saying has it, “If he beats you, it means he loves you.”

Prior to the enactment of the law, domestic violence was already a pervasive problem in Russia. Although data is scarce, Interior Ministry statistics reveal that 40 percent of all violence crimes in the country are committed in family surroundings. This translates to approximately 36,000 women being beaten by their partners every day, and 26,000 children being assaulted by their parents every year. An estimated 14,000 women are killed from domestic violence every year.

In the United States, which has about twice the population of Russia, about 1,000 women are killed by domestic violence every year.

These numbers are almost certainly lower than the true number of domestic violence victims. Domestic violence is, internationally, a chronically underreported crime. In countries such as Russia, where reporting is actively discouraged, underreporting is surely an even larger issue.

These shockingly high numbers reflect a general cultural acceptance of domestic violence. A minority, but sizeable portion, of Russian citizens recently polled (19 percent) said “it can be acceptable” to hit a family member “in certain circumstances.” Another poll showed that 59 percent of Russians were in favor of the law, with just 17 percent “fully against it.”

This sentiment is echoed in popular culture, said Alyona Popova, an activist and women’s rights advocate. “Traditional, or rather, archaic values have become popular again.” Despite high-profile stories of abuse among female actresses and journalists, commentators tend to blame the victim with intimations that they “most probably provoked” it, “were asking for it with frivolous behavior,” or “knew who they were marrying and should have known better.”

This blasé attitude towards domestic violence can be seen in an article printed in a Russian newspaper just ahead of Putin signing the measure into law. “[A] new scientific study is giving women with irascible husbands new grounds to be proud of their bruises, insofar as women who are beaten, biologists confirm, have a valuable advantage: they’re more likely to give birth to boys!”

“Women aren’t supposed to be able to do and achieve things on their own,” said Popova. “Society tells women to get married in order to let their husbands decide things for them. If a man beats you, it is because he is stronger and has the right to beat you, and you should consider yourself lucky to be married in the first place.”

If a woman does leave her abusive husband, it is not uncommon for relatives to disown her. “They would say that keeping the family together and standing behind the father of her children is more important,” said Larisa Ponarina, deputy director of the Anna Center, a nonprofit helping victims of domestic violence.

Russian police, too, tend to employ a hands-off approach to domestic violence calls in the belief that domestic violence is a family affair. Anecdotal reports say that police only intervene if there is a murder. As an example, Russian prosecutors are investigating a police officer who took a call from a woman who reported her boyfriend’s violent behavior. The police responded that they would come if she was killed. Shortly afterwards, she was.

The Alarming Lack of Protections for Russian Women Before Passage of the Law

Even before this law officially turned a cold shoulder on victims of domestic violence, Russia lagged far behind the rest of the developed world in women’s rights.

Russia is one of the few countries that have no civil laws allowing women to get restraining orders or emergency protective orders, despite their proven effectiveness. There are only 20 state shelters for women of domestic violence across the entire country of Russia. Moscow, home to 11 million people, has one state-funded shelter.

Russia joins Azerbaijan and Armenia as the only members of the Council of Europe who failed to sign the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence. Attempts to introduce Russia-specific domestic violence laws have languished in the State Duma, not even coming up for a vote.

International organizations, such as the United Nations and Amnesty International, have spoken out about the alarming state of women’s rights in Russia, including the tendency to stay idle in the face of domestic violence. Yet they are largely ignored.

The Law Leaves Vulnerable Populations Even More Exposed

Victims of domestic violence already face numerous hurdles. As explained above, they face pressure from family, the general public, police, the church, and lawmakers to keep the incident to themselves.

Even if they attempt to surmount these nearly insurmountable hurdles, the prosecution of domestic violence is made even more difficult because it requires private prosecution. With the exception of those few months between the Supreme Court decision in the summer of 2016 and the passage of the new law, the onus of prosecution falls to the victim. The victim is required to collect evidence, navigate the bureaucracy of the court system, and present her case. “It’s the circles of hell, it goes on and on,” said Natalia Tunikova, who tried unsuccessfully to prosecute the man who abused her.

“Domestic violence is a system which makes it difficult for a woman to seek help,” said Irina Matvienko, who runs Russia’s only domestic violence hotline.

Now prosecution is made even more difficult by the false proposition that domestic violence is only (legally) harmful if it results in serious injury—defined as requiring hospital treatment.

But focusing on the extent of violence inflicted is a dangerous move, and one that ignores the underpinnings of the dynamics of domestic violence.

Meg Garvin, Executive Director of the National Crime Victim Law Institute, an organization dedicated to the advance of victims’ rights, noted that “the change in law seems to rest on a fundamental misunderstanding of intimate partner violence.”

Garvin explained: “The dynamic at play in IPV [intimate partner violence] is not one that necessitates physical abuse at every turn. Rather, perpetrators abuse their victims in myriad ways from limiting access to finances to withholding citizenship or work documentation, to isolating them from family, friends and resources to verbally abusing them. Each of these attacks is a form of violent control that harms the victim.”

By focusing on only extreme physical harm, Garvin says, the law acts to “foster a culture that devalues the personhood of the victimized and encourages abuse. It represents a return to a time of silent suffering and should not be condoned.”

Anna Kirey, deputy director for Russia and Eurasia at Amnesty International, said of the law: “This bill is a sickening attempt to trivialize domestic violence, which has long been viewed as a non-issue by the Russian government. Claims that this will somehow protect families or preserve traditions are ludicrous—domestic violence destroy lives.”

An Uptick in Domestic Violence Already

Despite the backdrop of apathy toward victims of domestic violence, the passage of this law creates official sanction to fail to respond to domestic violence calls. Matvienko said that the bill “is not going to improve the situation to say the least.”

In addition to further increasing the likelihood that women will not report in the first place, it also is likely to—and in fact already has—led to an increase in incidents of domestic violence.

In Yekaterinburg, the fourth largest city in Russia, reports of domestic violence have increased 133 percent since the law was enacted. Police have responded to 350 incidents of domestic violence per day, compared with 150 before the legislation.

“Before, people were afraid of criminal charges—this acted as some kind of safety barrier,” said Yevgeny Roizman, the mayor of Yekaterinburg. “People got the impression that before it wasn’t allowed, but now it is.”

Opponents of the law intend to remain vocal in the face of the aftermath from the law. Above all, they want to make clear one important point about domestic violence. As Matvienko said, “It’s not a traditional value. It’s a crime.”

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads