America is Hard to See

That’s the title of the current exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The name comes from Robert Frost’s 1951 poem of the same name, originally published in The Atlantic magazine. In the poem, Frost takes Christopher Columbus to task for not recognizing the enormous possibilities of his “discovery.” Instead, Frost considers Columbus a negative role model for future generations of Americans who

… would have to put our mind

On how to crowd and still be kind.

Reading these lines, one can’t help but think about the crowds pouring into the Whitney since the new building opened in May. Renzo Piano’s design beautifully showcases the collection (of its 22,000 pieces, about 650 are on display) and, from its patios and capacious windows, the city itself.

With so many works from the permanent collection now on display, it’s hard to take it all in. Like Frost’s America, smaller works in the exhibit are “hard to see.” So you could easily miss gems like the two untitled drawings by Idaho-born James Castle.

Untitled (Farm Scene with Road) Untitled (Interior with Stove and Wood Box)

Located on the seventh floor, right next to Grant Wood’s study for the mural “Breaking the Prairie” (in the room of the same name), reside these unpretentiously eloquent drawings. Each is less than a square foot in area and depicts a rural scene (one interior, one exterior) from artist James Castle’s life. With very little education (and no formal art training), Castle created thousands of such drawings over 70 years. They display a mastery of perspective that accurately portrayed the world he saw around him. His work is all the more remarkable because of the material Castle used to create them: soot and spit on found paper.

An Artist Against All Odds

Castle was born profoundly deaf in 1899. He may have learned to read while attending the Gooding School for the Deaf and Blind (in southeastern Idaho), but he did not speak, use sign language, lip-reading, writing, or communicate in any traditional sense. Instead he used art as his primary means of expression.

His father was the local postmaster and operated the general store out of the family home in Garden Valley, ID. His mother was a midwife. Castle figured out that by scraping the soot from the family’s wood burning stove (perhaps even the one displayed in “Interior with Stove and Wood Box”) and mixing it with saliva on the lid of a glass jar, he could mimic the effects of graphite or charcoal. He applied the mixture using the most rudimentary of tools including sticks whittled to a point, old nails and apricot pits. Sometimes he dipped rags in the mixture and wiped them along the surface to achieve shading with tonal washes.

Undated Art

Neither of the Whitney drawings feature a title or a date. In fact, none of Castle’s works do. Any title, such as “Farm Scene With Road” above, was arbitrarily assigned by curators in order to differentiate the works, and Castle never dated any of them. Yet, art historians have been able to piece together only a rough chronology by examining the materials that he used.

For instance, chemical analyses of some of his drawings in color show he combined Crayola and Little Lulu-brand wax crayons. Since Little Lulu crayons were copyrighted by the Milton Bradley Company in 1948, these works could only have been created after that time. Likewise, Castle used wax-coated food cartons as support for some drawings (a support is the surface on which a work is created). Since this type of carton was not commonplace until the 1950s, these works can also be dated to later in his career. Similarly, some drawings were created on the back of his niece’s elementary school homework papers, which dates those works post-1930 when he moved in with his sister and her family. Of the Whitney’s drawings, there don’t seem to be any markings that would allow curators to identify a date.

In the case of “Farm Scene With Road,” the support appears to be the lid to a cardboard box. Notice the upper corners where a piece of the support appears to be missing. It looks as if this is a box top (imagine a sneaker box) where the corners have been pulled apart

and flattened. For “Interior with Stove and Wood Box,” the upper right hand corner dips lower than the left. With both lower corners rounded, this sheet could have originally been a place mat from a local diner torn in half.

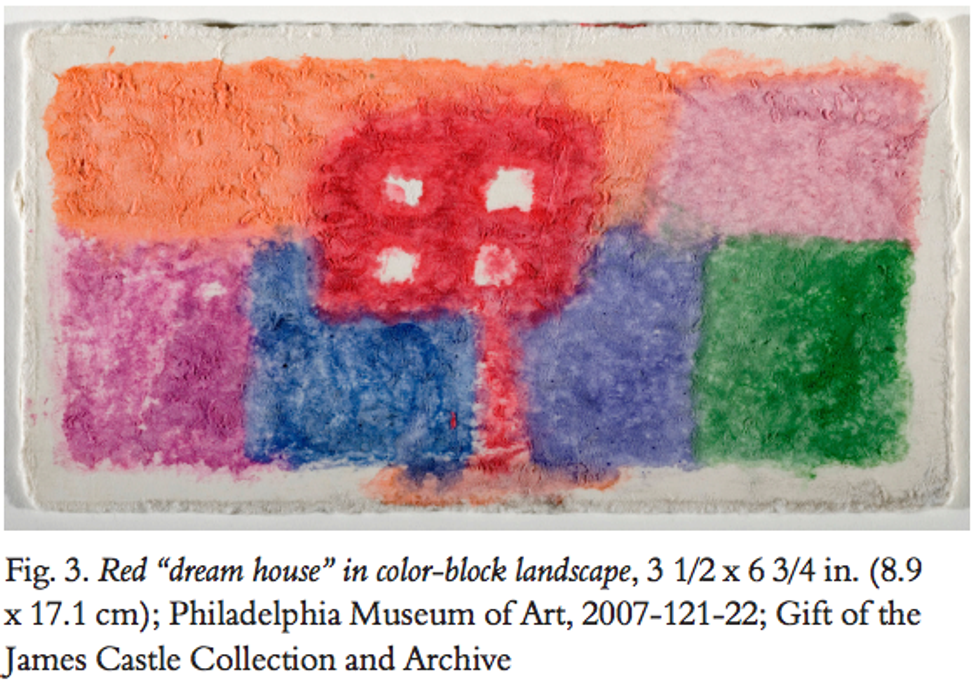

Such a guess is as good as anyone’s. Castle used to forage through the family garbage for paper to draw on. Once he started foraging through neighbors’ trash, they began bringing scraps to him daily. He used any kind of paper he could find, including advertisements torn from magazines, discarded envelopes, flattened matchboxes and packaging from food products such as butter purchased from the local store. On the left below is one of Castle’s drawings in color; on the right is the back side (called the verso in art history terminology) showing what the support actually was.

Just Plain Folk

Art historians define folk art as any work typically produced by untrained, often anonymous artists, usually working in isolation from cultural art centers or communities. This is certainly true of Castle who had only five years of schooling (at Gooding, he was considered “uneducable” and “illiterate”) and who would have remained anonymous if not for his art student nephew, Bob Beach.

Once his mother died, Castle spent the remainder of his years living with his sister, her husband and children on the Castle family’s subsistence farm in Boise, Idaho. In the 1950s, Beach studied at the Museum Art School in Portland, Oregon. When he returned home, he suggested to family members that Castle’s work (which included drawings, handmade books and assemblages) could be considered “art.” Beach took some drawings back to Portland to show his professors. This launched Castle’s recognition as an artist in regional museums and art galleries.

Castle’s work, however, exceeds what is usually called folk art. Chief among the characteristics of folk art are highly decorative design, bright bold colors, flattened perspective and strong forms in simple arrangements. While the piece shown above demonstrates these characteristics, the Whitney drawings are far more advanced, displaying an intuitive understanding of proportion and perspective that are remarkable for an untrained artist.

With “Farm Scene with Road” Castle has mastered the technique of single point perspective so that all of the diagonal lines converge on a single vanishing point about a third of the way down the right edge of the support. Linear perspective is an artistic concept developed during the Renaissance to simulate three dimensions on a two-dimensional canvas. In order to achieve it, certain rules must be followed, most importantly that parallel lines converge as they recede toward the horizon. Castle displays an intuitive understanding of this

principle by having both sides of the dirt road, the fence lining the farm property, and the treeline (beginning at the left part of the top edge) all converge toward a point along the right edge of the drawing.

“Interior with Stove and Wood Box” displays a sure command of place and surroundings. With a stove set away from the wall (we can tell by the shape of the flue, which contains a perpendicular section of pipe) and the door occupying a spot along a second wall, this feels like an actual dwelling; most likely one of the only three homes Castle lived in during his life.

In contrast to fine art, folk art is often utilitarian and decorative, rather than purely aesthetic, and yet Castle’s drawings appear to be “art for art’s sake” even if they were meant for only an audience of one. In an old wooden bunkhouse that he used as a studio, Castle hung his drawings on the walls salon style (see below) and curated his own exhibitions. Many of the drawings still exhibit holes from the nails he used to hang them.

When Castle died in 1977, his family found thousands of drawings, books and assemblages. They were stored in his studio, as well as in the barns, sheds, attics and walls of the family property. Since he couldn’t write, Castle didn’t keep a record of the works. Instead he lovingly wrapped similarly sized works in small pieces of cloth for safekeeping, unseen by but a few people.

Today, Castle’s work appears every day in the collections of almost two-dozen museums, including the Whitney and MOMA in NY, and the Art Institute of Chicago. A retrospective in 2009-10 travelled to three cities including Philadelphia, PA, and Berkeley, CA. Earlier this year, the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC presented a major Castle show; and Castle’s work features prominently in a group show presented by the American Folk Art Museum that began touring to six cities in April.

The Whitney’s expansion allows visitors to examine works by artists who otherwise would have remained under wraps. The size and scope of the current exhibition makes America a little easier to see. But you need to get there before September 27 when it closes in order to see them.

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads