DIGEST [NPR, Christian Science Monitor, Washington Post, Smithsonian, EWG]

A key ingredient in many sunscreen products is contributing to the rapid decline of coral reefs around the planet, according to findings in a new study published in the Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. Scientists, including researchers from the United States and Israel, found high concentrations of oxybenzone near coral reefs in Hawaii, Israel and the Caribbean. The ingredient has been found to damage or kill the delicate reef structures. However, the chemical can be devastating even in low doses: The Christian Science Monitor reports that just a tiny amount of oxybenzone — 62 parts per trillion, or a drop of water in six Olympic-sized swimming pools — can be toxic to fragile young coral. In higher concentrations, it can also prove fatal to adult coral.

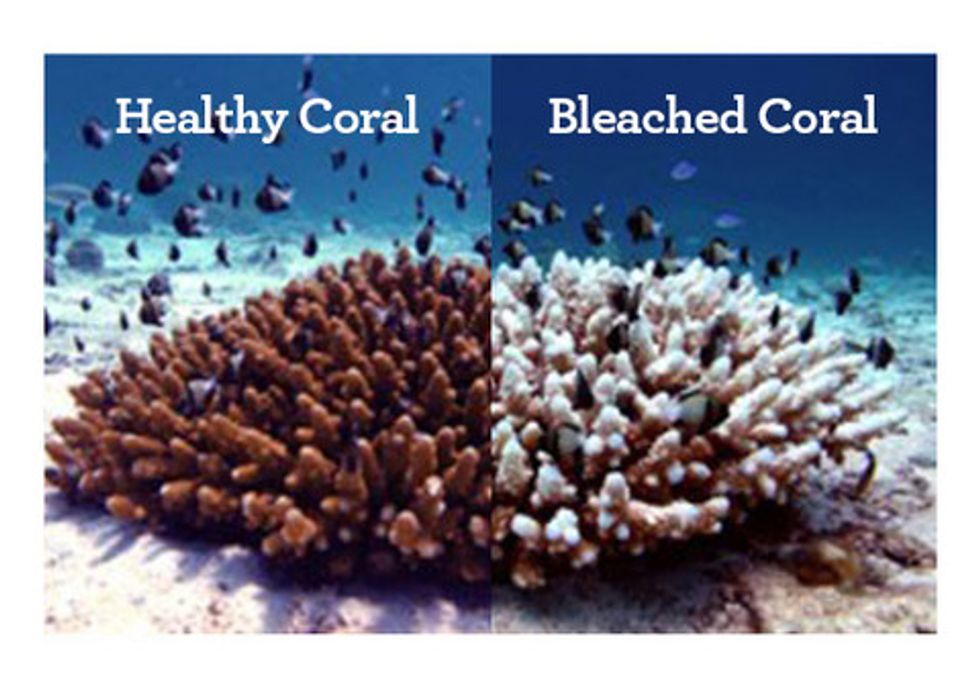

Oxybenzone damages coral reefs by breaking down the coral material, robbing it of life-giving nutrients and turning it ghostly white in a deadly condition known as coral bleaching, the Monitor reports. The chemicals can also coat and encapsulate the algae, leading to die-offs.

[post_ads]

Coral reefs are becoming “bleached” due to another factor: The warming seas. Earlier this month, the Washington Post reported that a massive, worldwide coral bleaching event is underway. Coral bleaching occurs when warm ocean waters stress the reefs and cause them to shed the symbiotic algae that provide color and nutrients to the structures. Without these algae, the whitened coral can die off.

Reefs that are already suffering due to sunscreen-borne pollutants, however, are particularly vulnerable to warming waters. Nancy Knowlton, an expert on coral reefs with the Smithsonian Institution, told the Post, “No reefs that experience unusually warm waters are likely to escape unscathed, but reefs already suffering from overfishing and pollution may have a particularly rough time recovering, based on what we have learned from past bleaching events.”

Mark Eakin, who heads NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch, told the Post that 95 percent of all U.S. coral reefs are expected to see ocean temperatures that can lead to bleaching sometime

this year, and 60 percent are expected to be “hit with severe thermal stress and we’re going to see a lot of corals dying.”

Sensitive Beauty

Coral reefs are unique, complex ecosystems comprised of calcium carbonate structures secreted by corals. Sometimes called the “rainforests of the sea,” coral reefs provide homes to 25 percent of the world’s marine species, including fish, anenomes, mollusks, sponges and crustaceans. Their beauty ironically inspires millions of travelers to swim in reef waters, adding to severe pressures borne from a host of human activities. Sunscreen contamination is but the latest threat the reefs endure in the face of our activities.

Destroying the Things We Love

Even if you never get in the ocean, the sunscreen you apply on land may ultimately make its way into the wastewater system. In coastal regions, when that wastewater is discharged into the ocean, it can damage coral reefs, and disrupt the development of fish and other wildlife.

“Oxybenzone pollution predominantly occurs in swimming areas, but it also occurs on reefs 5 to 20 miles from the coastline as a result of submarine freshwater seeps that can be contaminated with sewage,” says Omri Bronstein, a zoologist from Tel Aviv University and one of the study’s principal researchers, in the Christian Science Monitor.

Some 14,000 tons of sunscreen lotions wind up in coral reefs around the world each year, reports NPR; popular beaches in Hawaii and the Caribbean have much higher concentrations according to seawater tests. In the U.S. Virgin Islands, the concentration of

oxybenzone is 23 times higher than the minimum amount that can prove toxic to corals, the researchers found.

The Caribbean has suffered tremendous reef loss and the researchers are urging visitors to take action now. "The use of oxybenzone-containing products needs to be seriously deliberated in islands and areas where coral reef conservation is a critical issue," co-author Craig Downs said, according to the Washington Post. "We have lost at least 80 percent of the coral reefs in the Caribbean," Downs said. "Any small effort to reduce oxybenzone pollution could mean that a coral reef survives a long, hot summer, or that a degraded area recovers."

Reef-Friendly Alternatives

More than 3.5 million people are diagnosed with skin cancer every year, according to the American Cancer Society. Look at it this way: Sunshine can kill, and sunscreen can be a powerful defense. But if your sunscreen is killing the ocean, is it your pelt versus the coral reefs? Maybe not. According to the National Park Services for South Florida, Hawaii, U.S. Virgin Islands and American Samoa, there’s no completely “reef-friendly” sunscreen, but beach visitors should consider sunscreens that contain natural ingredients like titanium oxide and zinc oxide, often found in children’s sunscreens, as alternatives to those with oxybenzone, reports NPR.

Another option: Wear sun-protecting clothing, including long-sleeves, hats, and rash guards in the water, to reduce the risk of harm to coral, the researchers say. Clothing is the single most effective measure people can take to prevent harmful ultraviolet rays from penetrating the skin, according to the Skin Cancer Foundation, which recommends fabrics with a tight weave for higher protection. Many companies offer clothes specifically engineered to block UV light. In the end, you may be doing yourself a favor. Environmental Working Group lists oxybenzone as an ingredient to be avoided, due to skin irritations, allergens and hormone-disrupting activity. The organization publishes an annual Guide to Sunscreens that ranks products based on health and safety measures. As it turns out, what’s better for you is also better for life in the sea.

Featured image via Flickr user NPS Climate Change Response

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads