When grocery shoppers choose shelf-stable “boxes” of organic almond milk over refrigerated plastic jugs of conventionally-produced cow milk, they believe they’re doing something good, not only for their own health, but the environment. But the sobering truth is that if shoppers happen to be in a chain supermarket, a “USDA Certified Organic” label on a box of almond milk doesn’t mean what it used to. In fact, some organic farmers now consider the label so meaningless, they refuse to use it on their products.

Organic food production is no longer limited to small, privately owned farms. Consumer demand for organic foods rose sharply over the last decade and a half, from U.S. sales of $6.1 billion in 2000 to $35 billion in 2013. Not surprisingly, this trend resulted in a dramatic change in the organic agricultural landscape. Multinational corporations including Coca-Cola, Cargill, ConAgra, General Mills, Kraft, and M&M Mars have taken over what has become an increasingly consolidated — and profitable — sector of the food industry.

What do all these words mean?

Organic. Local. Seasonal. Sustainable. Many use these words interchangeably, or assume--without any real basis for doing so--if one is true, the others necessarily follow. Marion Nestle, a professor of nutrition, food studies and public health at NYU, defines these terms as follows:

- “Organic” means crops grown without artificial pesticides, fertilizers, GMOs, irradiation, or sewage sludge, and animals raised without hormones or antibiotics. Certified Organic methods follow specific rules established by USDA.

- “Local” means foods grown or raised within a given radius that can range from a few to hundreds of miles (you have to ask).

- “Seasonal” refers to food plants eaten when they are ripe (and not preserved or transported from where they were grown).

- “Sustainable” means -- at least by some definitions -- that the nutrients removed from the soil by growing plants are replenished without artificial inputs.

Environmental and health writer Jennifer Chait explains the difference this way. “USDA Certified Organic is a real certification. Sustainable is not. While there is no certified label or official policy that describes sustainable, most people consider sustainability a philosophy that describes planet protective actions that can be continued indefinitely, without causing damage to the environment.” However, Chait goes on to explain that

To read more, continue to the next page.

“sustainable farming is not just a philosophy. Sustainability is observable and measurable via economic profit, social benefits for the community and environmental conservation.”

The dangers of monocrop farming

Organic food is a lucrative venture for big corporations because their size allows them to take advantage of economies of scale, more so than mid-size independent organic companies. This profitability is made possible by large production operations, which represent a growing shift away from sustainable practices, in favor of corporate profits and the rise of “Big Organic.”

Consider the organically-grown almonds used in almond milk. Transitioning conventional fields to organic is a three-year process. Once planted, almond tree orchards take another three or four years to bear fruit. Due in part to the long-term nature of almond crops, many large farms producing organic almonds use “monocrop” agriculture, also known as monoculture farming, where the entire space is reserved for a single crop, as opposed to rotating through other crops or growing a variety crops on the same land.

Now consider the first criterion for “organic” as defined in 1995 by the USDA National Organic Standards Board (NOSB):

“Organic agriculture is an ecological production management system that promotes and enhances biodiversity, biological cycles and soil biological activity. It is based on minimal use of off-farm inputs and on management practices that restore, maintain and enhance ecological harmony.”

Conventional farmers protect their crops with synthetic pesticides and herbicides. Since NOSB organic standards prohibit the use of toxic chemicals or genetically modified organisms (GMOs) to control insects, diseases, and weeds, organic farms must rely on compost and biological pest control. Small and mid-size organic farmers plant relatively small plots with carefully selected combinations of crops that help control pests and enhance soil fertility. This approach, called polyculture, has a history of sustainability.

Preserving biodiversity

Biodiversity refers to the variety of life-forms found within a specified geographic area. In relation to organic farming, Jennifer Chait notes, “biodiversity is important for successful integrated pest management (IPM), soil conditions, overall growth of crops and maintenance of organic livestock. In most cases, a farm with greater biodiversity, meaning a greater number and variety of plants, animals, birds and insects, will be more naturally stable than a farm with less biodiversity.”

In direct contrast, growing thousands of acres of one crop, such as almond trees, eschews biodiversity and crop cycling and, over time, reduces soil quality. This is

To read more, continue to the next page.

counter to the NOSB’s definition of organic, yet large-scale organic farms often use these practices — and big food companies sell their products with a “certified organic” label.

Nor any drop to drink

Monoculture farming of organic foods is not nearly as sustainable as the polyculture approach. Take almond production. All domestic almonds are grown in California, where 860,000 acres were dedicated to almond orchards in 2014. Of this acreage, roughly one percent (7008 acres) was certified organic. Tree crops are long-term, and they need water every year regardless of weather conditions. Farmers who have devoted a great deal of acreage to almonds (or any other trees) are unable to adapt to water shortages such as the well-publicized drought in California. Smaller organic productions, with a polyculture of trees and annual crops, might choose to forego planting vegetables in order to redirect water to their trees.

Large-scale tree farmers, however, have few options: let their trees die, rely on federal and state irrigation allotments, or pay hundreds of thousands of dollars to buy water. The third option involves purchasing water from other farmers or investing in million-dollar drilling rigs to dig private wells. Tapping into California’s dwindling groundwater in the midst of a drought is, arguably, the antithesis of sustainability.

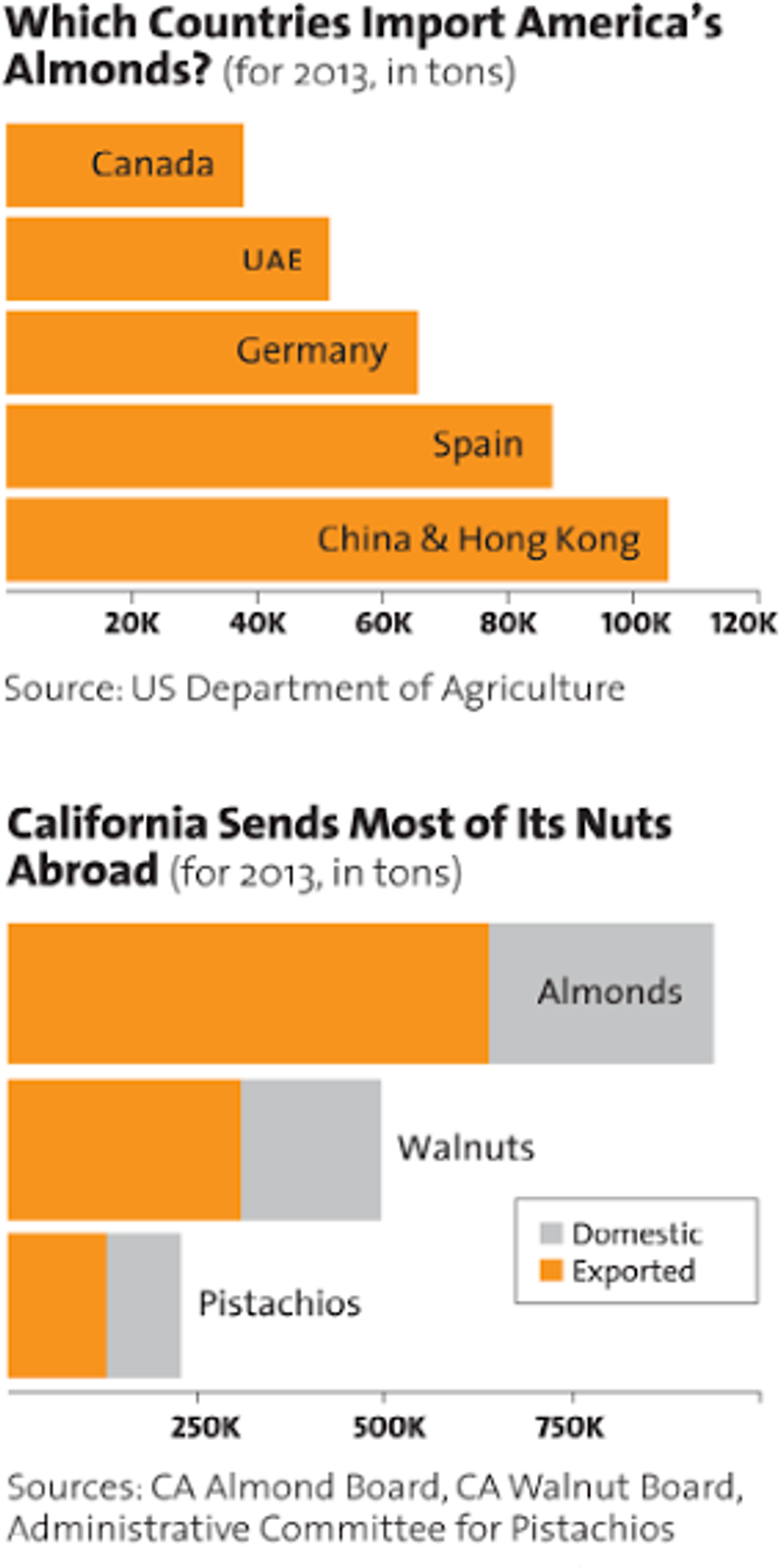

“Nonorganic” distribution practices

Big Organic is unsustainable for reasons other than monoculture. Unless locally sourced, organic products in chains such as Walmart or even Whole Foods have been refrigerated and transported long distances. This distribution model uses as much fossil fuel as conventional food suppliers, and it’s not limited to domestic distribution. Not surprisingly, almonds are a perfect example. California is the only state that grows almonds commercially, producing 82 percent of the world’s supply. East Coast consumers who have a taste for organic almonds can buy them only after they’ve been shipped cross-country. What’s more, about 70 percent of California's almonds are sold overseas.

The NOSB’s organic guidelines don’t specifically address distribution practices, though the second criterion includes the following:

“The principal guidelines for organic production are to use materials and practices that enhance the ecological balance of natural systems and that integrate the parts of the farming system into an ecological whole.”

Long-distance domestic and international transport of organic foods does nothing to minimize environmental impact, which is integral to enhancing — or, at the very least, maintaining — ecological balance. In this case, Big Organic is technically in compliance with organic standards. Still, their distribution model illustrates a blatant disregard for environmental health, favoring profits over sustainability.

Served with a side of pollution

Something that may surprise consumers accustomed to thinking of organic food as healthier and cleaner than nonorganics is encapsulated in the third NOSB guideline:

“Organic agriculture practices cannot ensure that products are completely free of residues; however, methods are used to minimize pollution from air, soil and water."

Essentially, this says the food should be clean but doesn't really have to be.

Choosing profits over people

In addition to using distribution channels similar to those of conventional farmers, large-scale organic productions also employ migrant workers. Again, while these labor practices are not directly proscribed in the NSOB’s guidelines, the fourth and final criterion includes the following:

“The primary goal of organic agriculture is to optimize the health and productivity of interdependent communities of soil life, plants, animals and people.”

To read more, continue to the next page.

The labor-intensive nature of organic farming is one reason that organic food is more expensive than conventionally farmed produce. Raising crops without chemical pesticides and herbicides requires more hands-on work, including weeding, application of organic fertilizers, and manual pest control. Small and mid-size organic farms are often run by family members and long-term employees who earn a living wage and must price their products accordingly.

Big Organic must employ farm workers on a much larger scale, and its misuse of migrant labor is largely consistent with that of conventional farms. Basic human rights are integral to the health of communities, but migrant workers are not healthy, nor are they usually part of interdependent communities. In choosing profits over people, Big Organic fails yet another litmus test for sustainability.

Enforcing organic standards

When the NOSB organic standards replaced local and regional guidelines in 2002, farmers who sold products as organic were required to go through a national certification process so expensive and time consuming that many smaller organic producers simply stopped using the word organic. These farmers continue to employ growing practices that meet or exceed the national organic standards, but they are not legally allowed to label their products organic.

Meanwhile, multinational corporations enjoy a distinct laxity in the enforcement of current organic standards. This invites the question: who — and what — benefits most from the USDA’s implementation of organic regulations? It’s certainly not small to mid-size organic farmers, nor the environment. The obvious answer is agribusiness, or Big Organic, something food advocates have been talking about for the last decade. As food advocate Michael Pollan mourned in a 2010 interview:

“Organic is in danger of being co-opted. I've been on organic factory farms, and if most organic consumers went to those places, they would feel they were getting ripped off. I think organic risks a real crisis of perception if the values that they're selling don't accurately reflect the practices they're engaging in. They're organic by the letter, not organic in spirit."

Organic vs. sustainable

Health-conscious consumers who are also concerned with sustainability would do well to heed Pollan’s words when choosing which food products to buy. There is an important distinction between “organic” and “sustainable.” Those words represent different concepts that are often used interchangeably, but shouldn’t be. The most basic interpretation of organic farming is a method of growing foods without the use of chemical pesticides, herbicides, fertilizers, and GMOs. Sustainability is a much more complicated notion, and one that cannot be reduced to a simple definition.

In other words, organic has become a certification, whereas sustainability is a philosophy, or even a way of life. Here, the operative word is “life,” because without enough farms whose productivity can be sustained for generations, what will happen to our food supply?

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads