Over three decades of service, Justice Antonin Scalia became one of the most polarizing members of the United States Supreme Court--so much so that, according to recent conspiracy theories, it may have gotten him killed… by Leonard Nimoy.

Nimoy died last year at the age of 83 after a long battle with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Yet even spoof internet conspiracy theories had many folks believing that, rather than dying, Nimoy assumed leadership of the elusive Illuminati, an organization that allegedly conspires in global affairs. Choosing to fake his own death, according to these theories, was an important part of his plan to consolidate power over liberal groups.

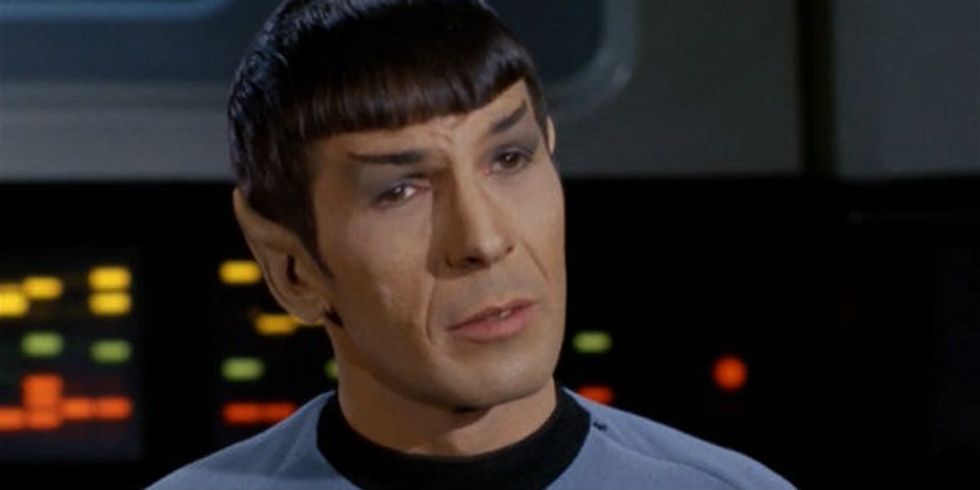

Nimoy’s place in pop culture in fact may have ensured his death would not only be mourned the world over, but questioned, just as Spock’s was in the Star Trek films. But this wouldn’t be the first time fiction bled into fantasy for his fans.

The Anti-Spock

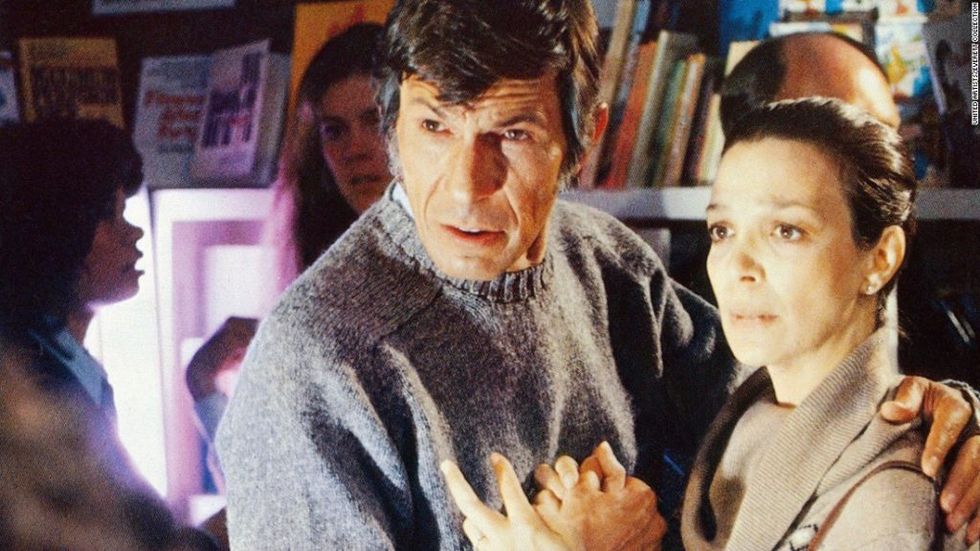

Dr. David Kibner has a dark secret: He’s not human. He’s actually an alien, successfully assimilated into a world where emotion is valueless. The pod people of Philip Kaufman’s 1978 Invasion of the Body Snatchers—who’ve arrived on Planet Earth via mysterious plant spores—have seen to that. Kibner stays silent, acting as a double agent in an attempt to convert his friends,

but they soon uncover the truth.

“I hate you,” says one.

Kibner’s reply is chilling: “There is no need for hate now. Or love.”

Dr. Kibner was played, in a rather inspired bit of casting, by the inimitable Nimoy, who had attained a massive cult following as Mr. Spock a decade prior.

As a Vulcan, Spock would be unaffected by love were it not for his half-human side. His romantic inclinations surfaced most notably in the episode “This Side of Paradise,” where he fell under the influence of plant spores that compelled him to express his feelings for a young botanist. These roles, then, represented extraterrestrial extremes: Spock (calm, good, yet struggling and susceptible to emotion) and Dr. Kibner (cold, evil, and utterly emotionless). Nimoy had successfully brought his career full circle.

With Star Trek, rarely has a marriage between a performer and his character been so absolute. To the world, Nimoy was Spock. But he also wasn’t Spock. He was, in fact, the anti-Spock, struggling privately to reconcile the merger of his celebrity with the intricacies of his personal identity. Nevertheless, he was not afraid to subvert his persona as an unemotional intellectual, as in the case of Dr. Kibner. Nor did he shy away from self-parody, as when he voiced a dispassionate Spock action figure in an episode of The Big Bang Theory.

Spock’s influence extended even to the Oval Office: President Obama professes to be a lifelong fan of Star Trek. Upon meeting Nimoy at a luncheon for prospective presidential candidates in 2007, Obama joked that it was “only logical” to greet him with the Vulcan salute, the universal symbol for “Live Long and Prosper.”

And if Spock, ever observant and cerebral, represents a voice of reason in an age of social turbulence,

Obama likely takes little umbrage from criticisms that he is distant—Vulcan-like—in his mannerisms and leadership.

The man who declared I Am Not Spock in a controversial 1975 autobiography reportedly “caught a lot of heat” for the assertion and would later pen a follow-up (I Am Spock) to address misconceptions that he was rejecting the character. That character was so beloved that fans would not accept Spock’s death in 1982’s Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan, and his famous death scene prompted many letters of protest to Paramount Pictures. Nimoy and the film’s production crew received actual death threats over the storyline. It seemed as if Nimoy would never escape Spock’s shadow.

“My folks came to the U.S. as immigrants, aliens, and became citizens,” he told students in a 2012 commencement speech at Boston University. “I was born in Boston, a citizen, went to Hollywood and became an alien.”

Going Boldly Beyond the Myth

Nimoy’s life and his artistic contributions, of course, went far beyond his struggle to differentiate himself from his iconic character. His fans wanted him to remain Spock forever—he’d wryly comply—but his sense of humor extended beyond the persona he occasionally lampooned.

In 1987, Nimoy directed a zany comedy titled Three Men and a Baby, starring Tom Selleck, Steve Guttenberg and Ted Danson, who was in the middle of his run on television’s Cheers. The film was sandwiched between a number of Star Trek outings which Nimoy also directed. Three Men and a Baby went on to become the highest-grossing film of 1987, in an film era dominated by jedis, space aliens, coming-of-age teen comedies and hockey-masked serial killers.

The success of Three Men and a Baby was enough to establish the man on the other side of the camera lens on his own terms. The film was not a counter to

Spock, though there is a certain poignancy to a comedy about three men and their general lack of domesticity. Nimoy was always keen to explore the theme of self-reinvention. In the end, the men’s experience of caring for a child challenged their perceptions of themselves and each other and revealed an unseen capacity for love, patience and understanding. This oddball comedy was an incongruous addition to the sci-fi icon’s filmography, but there could not have been a better vehicle to showcase a talent and introspectiveness shrouded by heavy typecasting.

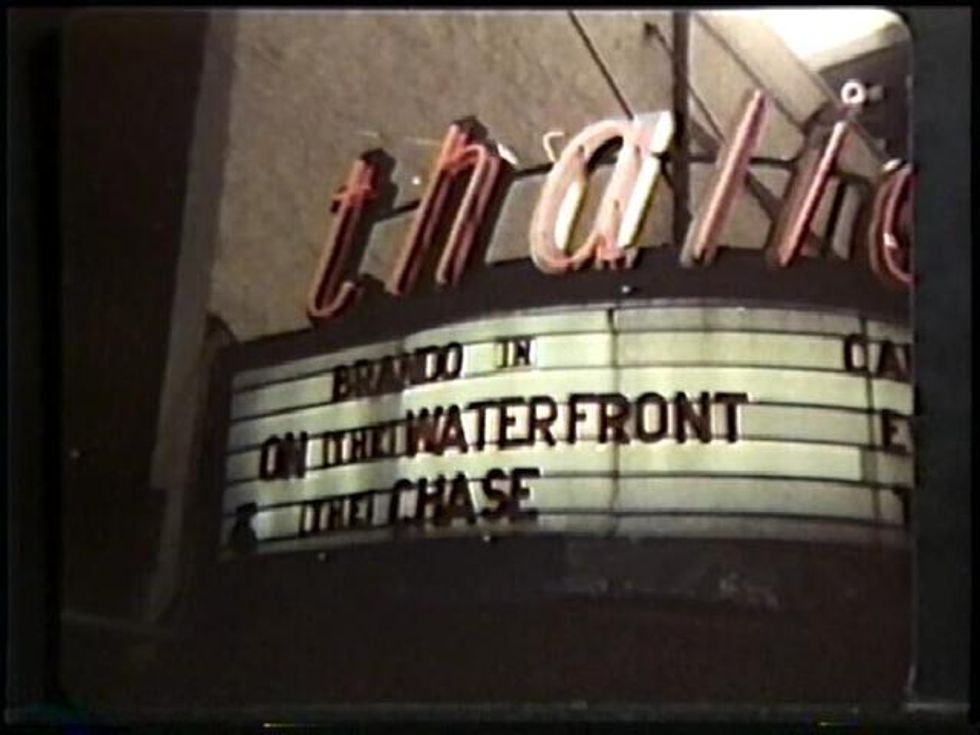

Nimoy’s talent and commitment to the arts helped shape Symphony Space, a performing arts organization with which he often performed at The Thalia, a movie theatre on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. At the Thalia, Nimoy regularly hosted readings of classic literature and staged his own plays for live audiences. The theatre was renamed The Leonard Nimoy Thalia in 2002.

“Leonard Nimoy was not only a brilliant actor who graced our stages many times over the past 30 years; he was also a visionary whose generosity made possible the transformation of the old Thalia movie theatre into the beautiful, state-of-the-art Leonard Nimoy Thalia theatre it is today,” said Cynthia Elliott, the president and CEO of Symphony Space, in a statement after his passing.

“I know people ask me what my secret self is, and I have to laugh,” Nimoy said in a 2009 interview with the Los Angeles Times. “I have no secrets left. I revealed it all a long time ago.” These secrets—or lack thereof—continue to provide insight into his impact beyond the final frontier.

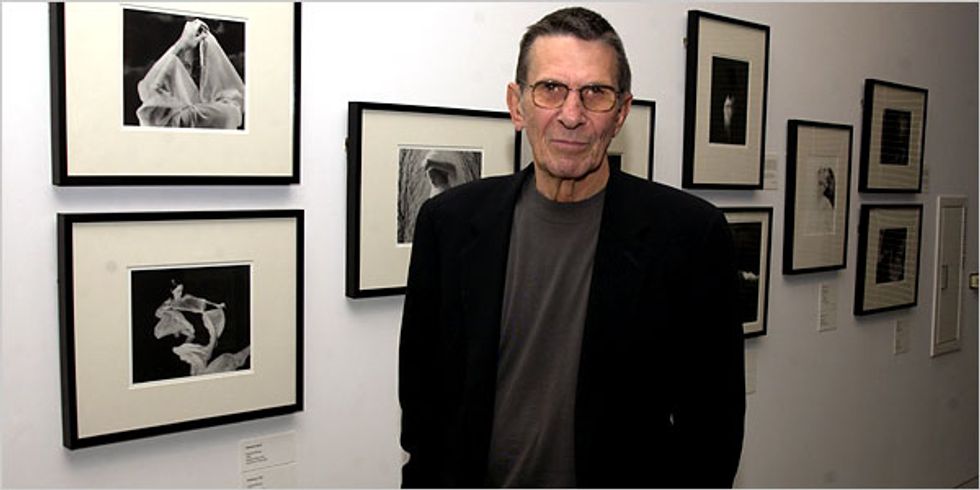

Nimoy was additionally a poet who published seven collections of poetry, including several poems in the celebrated online literary journal, The Hypertexts. He played troubled Dutch painter Vincent Van Gogh in

Vincent and embraced his Jewish heritage as Reb Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof. And in a culture where rail-thin models typically tread the catwalk, Nimoy celebrated more ample shapes in “The Full Body Project,” a collection of nude portraits.

His anti-Spock was nothing less than a graceful appeal of a Renaissance man who refused to rest on the overwhelming popularity of a single character.

Spock As A Global Inspiration

Nimoy found a recent audience on social media. On Twitter, Nimoy could measure the scope of his impact across cultures and continents. Many credited him with making geek culture not only acceptable, but cool, a hero to outcasts and to the misaligned, who defy socioeconomic boundaries. He often took the time to respond to fans who felt bullied or shamed, or outside the system. “Spock learned he could save himself from letting prejudice get him down,” Nimoy once wrote to a fan. “He could do this by really being himself and knowing his own value as a person.”

In the year since his passing, Spock, and the anti-Spock, live on in all those they touched. It is, as Nimoy might wryly note, only logical.

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads

Jim Carrey Just Shared His Latest Savage Anti-Trump Painting, and His New Nickname For Trump Is Perfect