The genius of couturier Charles James was almost lost to the threads of time, an all too common occurrence with some of history’s most accomplished yet eccentric figures. From his revolutionary designs and his scandalous sexual affairs to a famous friendship-turned-rivalry that marked the beginning of his unanticipated downward spiral, James a figure shrouded in both opulence and mystery, even to those who knew him best.

In an attempt to unravel the myths of his past, The Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art launched the “Charles James: Beyond Fashion” exhibit last summer where a handpicked selection of James’ most iconic and innovative designs were openly displayed for one of the first times since his death, giving a new generation a peek into the rise and fall of a legendary designer.

Uncovering a Legend

New York City, 1978. World-renowned couturier Charles James lies in his bed in Room 624 at the Chelsea Hotel on West 23rd Street battling bronchial pneumonia in his final days. Surrounding him are piles of his sketches and troves of small sculptures that he had crafted over the course of his 32-year career. At 73, he had amassed a library of creations, from one-of-a-kind couture gowns worth thousands of dollars to a massive collection of homoerotic sketches of the various men he privately entertained throughout his life. The treasures that he tucked away throughout his three sixth-floor rooms at the Chelsea that he used as office, workspace and living quarters were not only awe-inspiring, but a testament to the legacy he would leave behind.

Designing His Path

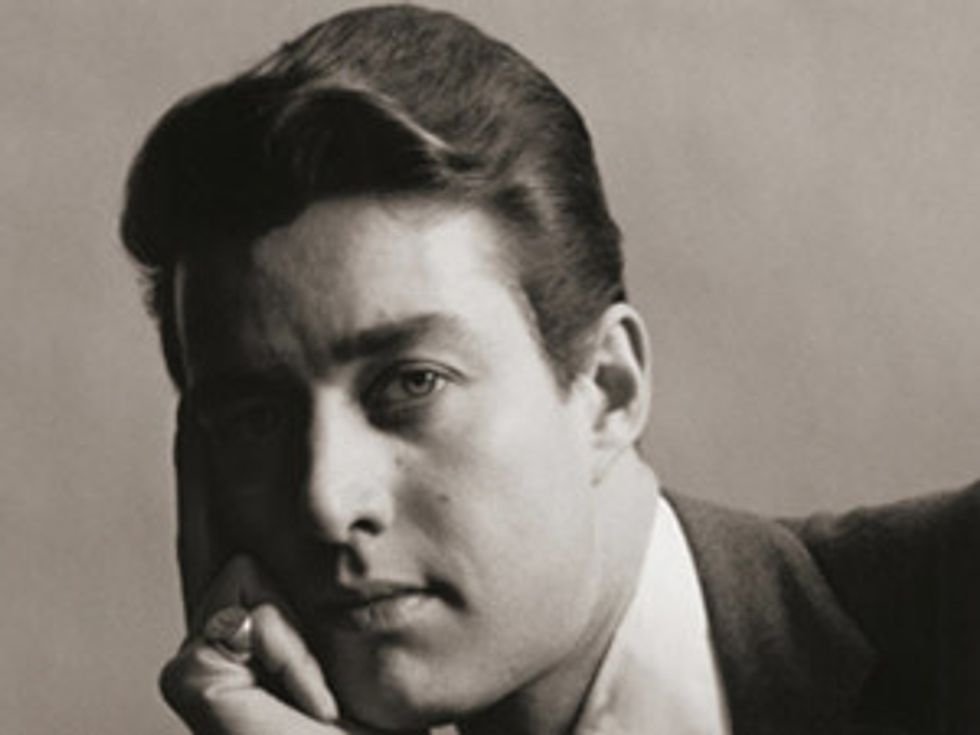

Born on July 18th, 1906, in Surrey, England, James grew up under the watchful eye of his British army officer father, Ralph Ernest Haweis James. At 13, he was sent to Harrow School, a prestigious English boarding academy for boys in northwest London. It was here he met Cecil Beaton, the soon-to-be famous English fashion, portrait and war photographer who would go on to win two Academy Awards in art direction and costume design for My Fair Lady in 1964. They formed a deep friendship which, combined with James’ overtly homosexual behavior, led to rumors that the two were much closer than merely schoolmates.

James was eventually expelled from the school for a “sexual escapade,” one of many, which did nothing to bolster his already strained relationship with his father. “I was thought by my father to be completely degenerate,” James says in “A 15-Hour Conversation with Charles James,” a string of exclusive interviews with longtime friend and society columnist R. Couri Hay. “One of [my father’s] concepts of degeneracy was my liking Picasso and reading Thomas Mann, yet when he died at 92, the volume of Thomas Mann’s A Death in Venice, the first publication in this country, was found in his library. He kept it. I’ve never really made it out.”

After being rejected by his family due to the ensuing scandal, James left England for Chicago where he opened his first hat shop at the age of 19. Fearing his London reputation might follow him to the States, he worked under the name “Charles Boucheron.” It wasn’t until two years later when he moved to New York and opened up shop in Murray Hill, Queens, that he

began to explore his interest in haute couture and dressmaking. After a short stint in the Big Apple, he moved back to Europe where he spent much of his time at the Parisian fashion houses, learning and perfecting high quality couture throughout the 1930s and went back to designing under “Charles James.”

The First American Designer in Paris

In 1937, James debuted his first show on the Paris runways, marking himself as the first American designer to bring a collection to Paris. A decade later, he returned to the City of Lights for what turned out to be one of the acclaimed fashion shows of his career. In that same year, Dior revolutionized the industry with his waist-wrapping “New Look,” a look that James had not only anticipated and featured in his new collection, but for which Dior himself was said to have credited James.

Cristóbal Balenciaga regarded James as "not only the greatest American couturier, but the world's best and only dressmaker who has raised haute couture from an applied art form to a pure art form." The Surrealist painter Salvador Dali, himself a close friend of James, added, “Charles’ white satin evening coat is the first example of a soft sculpture.” James’ designs revealed deep Surrealist influences.

His fans extended over oceans and backgrounds, from the French playwright Jean Cocteau, who lived across the hall from him in Paris and of whom James recalled, “I tried to hang myself once over a boy, but Cocteau cut me down,” as well as Virginia Woolf, who called his dresses “diabolical.” Charles James had become a revered name.

Life Amid the Glitterati

By 1950, James was back in New York City designing for movie stars, society’s elite and some of the most illustrious names of the era. His glittering client list included Queen Ena of Spain, Coco Chanel, Marlene Dietrich, Gypsy Rose Lee, Lady Diana Cooper, Dolores del Rio, Elizabeth Arden, Dominique de Menil, Babe Payley, Brooke Astor, Ruth Ford, Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney and the famed socialite Austine Hearst, who once said of the gowns James made her, “His dresses healed every flaw.” James’ motto was, “I give a woman the figure she wants but doesn’t necessarily have.”

A Charles James handmade dress in the 1950s landed anywhere between $6,000 and $9,000, the equivalent of about $60,000 in today’s markets, making his dresses not just part of high fashion, but unique and priceless works of art. Each dress was personally done by hand from start to finish, from the first pencil stroke of the design sketch to the final hem of the gown, designed for each client based on their body and how he envisioned the final result to look on them.

Despite driving some of his patrons to tears and sometimes taking a year to deliver a dress, James confided, “I loved my clients. People often didn’t know that. Dressing them was a

vicarious form of making love. I took delight in enhancing their beauty so that they could make a great impression on the men.” He also regularly raided his own closets so that his self-indulgent young assistants could enter the infamous Studio 54 in vintage-couture drag. James was living the life that designers dreamed of. Or so he thought.

Making Frenemies

Roy Halston Frowick, another up and coming designer who would eventually go by the single moniker of Halston, made his way to New York City in 1957 after a booming five-year stretch in Chicago. Within a year, he became the head milliner for Bergdorf Goodman. As his fame grew, he started to mingle with the Studio 54 crowd, including such luminaries on the social scene as Liza Minnelli and Bianca and Mick Jagger. This is where Halston met James in 1958, hiring him to help restructure clothing using James’ pristine couture methods a number of years later.

Already having known the prestige of the Charles James name, Halston began inviting James to collaborate with him, both in an attempt to bring his own designs to the next level and to help James, who was struggling financially as the cost of making his extensively designed gowns rose while his regular client list dwindled. The two worked on one of fashion’s first “ready-to-wear” lines, which eventually became the new industry stampede as other fashion designers clamored to jump on the new trend soon after its debut.

But Halston wasn’t interested in clothing that took months and months to make by hand, as was James’ specialty. In his interviews with R. Couri Hay, James reveals that, over time, he discovered that Halston’s rise to power was fueled by cutting corners and standing on the shoulders of designers who preceded him. Halston traveled the world buying other designers’ clothes and implementing improvements to his own designs based on his findings. Among those who were close enough to witness this was Hay himself, who recalls the designer telling him, “I’m just going to move this button a half-inch and change the collar a little bit, and then send it to Japan to copy; it’s a lot faster and cheaper than being Charles James and spending three years and $20,000 perfecting a sleeve.”

Needless to say, after 13 years of partnership and friendship, James’ opinion of Halston began to sour and their collaboration dissolved. Later, when Halston launched his ready-to-wear line and removed James’ name from the label, James accused the fashion mogul of stealing his designs and not giving him credit.

James remarked in retelling the story to Hay, “Halston is a middle-of-the-road man who would be better as a buyer in the store or a stylist. He knows how to select good things to copy but his passion has been to put his name on it. The word plagiarism is correct.”

The Beginning of the End

Soon after, James found himself in a downward spiral struggling to make ends meet. After Halston and his associates had him blacklisted from most of the fashion houses in New York, James was barely surviving on orders from his private clientele. In a final ignominy, the IRS forced him to close his shop due to his inability to keep his finances afloat or attract more paying clients. He first filed for bankruptcy in 1960. When asked what it was like to dress the rich, he threw his hands in the air and grumbled, “They never pay their bills on time. Therefore, neither do I.”

The years passed and by 1970, it had been 13 years since any of his clothes had last appeared in Vogue. The rumor was that Diana Vreeland, a great supporter of Halston and his designs, and longtime editor of Vogue and special consultant to the Costume Institute, was purposefully ignoring him and excluding him from the print and couture shows,

including one particularly prestigious Parisian haute couture show, showcasing how American designers had begun to produce clothing of the same quality as the most illustrious fashion houses in Paris. As the first American fashion designer who had not only managed to infiltrate the Paris houses but also mastered the craft, James was especially distraught to be blatantly excluded from the exhibition.

“Mrs. Vreeland had said that I hadn’t really worked out of Paris. Later, any proof that I had worked out of Paris would put her in the wrong,” James explained. “It’s a very foolish thing to have done and a very wrong thing to have done, to make enemies and give them reason to think of you as an enemy. It was a foolish thing of Mrs. Vreeland to leave me out of that show.”

In 1972, broke, tired and worn from his roller coaster of a career, James made his final collection inspired by his friend and artist Elizabeth Strong-Cuevas, whom he had known since she was a teenager. Cuevas remembers her times with James to this day as she told The Met just before the “Beyond Fashion” exhibit opened, “He was very funny. He was brilliant, I guess. He was passionate, he was jealous, and he adopted, probably, somebody like Millicent Rogers, and I think then he sort of adopted me.”

It was at this time, as he felt his career drawing to a close, that he wrote an article for Metropolis magazine, a tell-all exposé that accused Halston of plagiarism and called him a “thief” and a “copycat.” Mrs. Vreeland was also not spared from the vengeful diatribe, calling her the “the queen of perversity.” Although the write-up could not salvage his tattered career, it was his way of letting the world know that he and his livelihood had been sabotaged.

The Greatest Couturier in the Western World

Among the final words heard from James’ lips as they carried him out of the Chelsea Hotel, “I am what is popularly regarded as the greatest couturier in the western world.” James’ legacy became shrouded in myths and speculations, almost plunging his name into obscurity. But 36 years after his death, The Costume Institute launched its immense Charles James exhibition featuring fifteen of James’ most iconic gowns, including the legendary “Clover Leaf” gown he custom made for Austine Hearst in 1953 and was widely known to be his favorite of all his creations, and a number of his never-before-seen sketches, introducing the couturier to a whole generation who most likely had never heard of him.

James’ indomitable spirit and fashion genius has posthumously put him back on the lips of the fashion icons and elite alike. Before he died, he made a single wish for the future: “I would wish others who one day can influence fashion, having the guts and capacity to do so, live through me when I’m gone.”

His wish has certainly and finally come true.

SECONDNEXUS

SECONDNEXUS percolately

percolately georgetakei

georgetakei comicsands

comicsands George's Reads

George's Reads